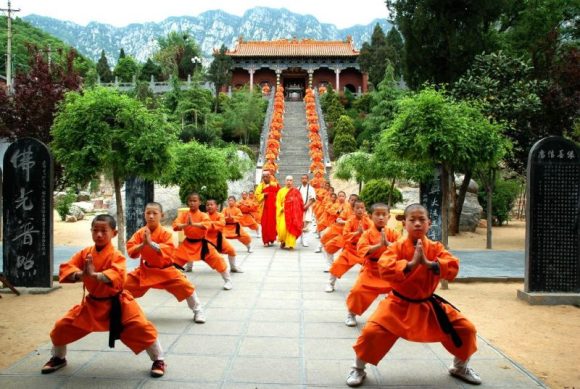

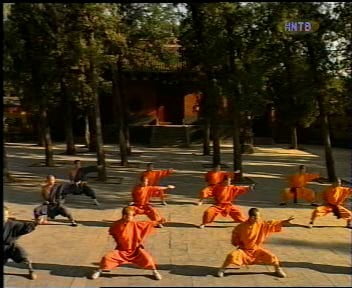

The history of the Shaolin Temples with its fighting monks has been a very long, exciting, and honored tradition with much political intrigue.Through the ages, the Shaolin Temples (north and south) have been built, burned down, and rebuilt many times. Even so, through all its tribulations, it has never ceased to be a training grounds and holy place for the monks. Out of about 1,500 years, it has been totally closed and deserted only a handful of years (and even then, monks trained there at night secretly). Shaolin is most famous for its deep knowledge and developments in all aspects of the martial arts.

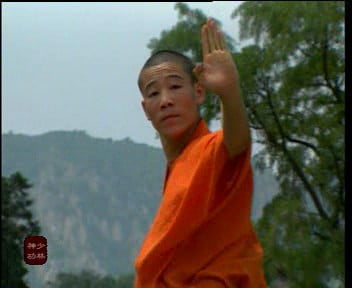

Shaolin’s fighting monks, of which at its peak numbered in the thousands, had a reputation throughout China for being highly honorable, most courageous, and greatly skilled. Shaolin’s fighting monks served as role models for the virtuous and spiritual warrior and sparked a huge interest in martial arts that influenced much of what we know today.

Shaolin’s fighting monks, of which at its peak numbered in the thousands, had a reputation throughout China for being highly honorable, most courageous, and greatly skilled. Shaolin’s fighting monks served as role models for the virtuous and spiritual warrior and sparked a huge interest in martial arts that influenced much of what we know today.

Oddly enough, the Shaolin fighting art’s came from a pacifist beginning: the merger of the spiritual philosophies of Buddhism and Taoism. The first and main Shaolin temple was located in Henan (Honan) province, along the north side of Shao Shih [shaoshi] mountain, and built by the royal decree of Emperor Hsiao Wien [Xiao Wen] during the early Northern Wei dynasty (386 – 534 AD) for an Indian Buddhist monk named Batuo (or Fo Tuo in Chinese). (He is most remembered today by his statue, which depicts a fat and jolly seated monk, the “Laughing Buddha”.) The temple originally consisted of a round dome used as a shrine and a platform where Indian and Chinese monks translated Indian Buddhist scriptures into Chinese, toiling both day and night.

Buddhism & Taoism in China

As early as the year 65 AD, the first Mahayana Buddhist community had settled in China along the ancient silk trade route between India and China. This settlement was built during a time that China was composed of many feudal kingdoms. Many of the common people as a result were on troubled times and had converted to the simpler and older beliefs of Taoism, which preached the individual search for a higher form of physical and mental existence based on withdrawing from daily man-made traditions and instead finding a path in the natural elemental and spiritual forces of life. Many had became disillusioned with the countless artificial rules of conduct decreed by Confucianism and Legalism, which believed in solving socio-political problems through regulations and laws. Taoism caught the attention of the common folk who already believed in the cycles of nature and the existence of spiritual forces, and it spread rapidly throughout China, especially in its southern regions.

Mahayana Buddhism also believed in the futility of worldly ways, but instead preached the endurance of suffering through spiritual pursuits such as prayer, scripture reading, and good works in order to reach the final emancipation promised by Nirvana (Pure Land of Bliss). When Buddhism reached China, it first attracted the attention of scholars, courtiers, and the nobility, appealing to their intellectual sensibilities. Thus, started the beginning of Indian culture and philosophy influencing Chinese custom and thought.

By the year 316 AD, China was divided into warring tribal states and much strife occurred as barbaric tribes invaded the north. The time period became characterized by a great revival of religious fervor of all types and many temples and shrines were built throughout the land. Buddhism gradually spread, as did Taoism. In fact, Buddhism became such a powerful force that violent power struggles broke out between adherents to Taoism and Buddhism.

Over time, Mahayana Buddhism in China and India became more entrenched in ritual and religious dogma. People believed that translating scripture and performing elaborate rituals and good works alone assured one of a place in ‘heaven”. Dhyana Buddhism developed in Southern India and it preached a return to purer spirituality and a more austere and conservative demeanor, where salvation could only be achieved by inward enlightenment. Material things were secondary and so was a blind following of scriptures, deities, and good works without true understanding of their intent.

Buddhidharma, legend has it, the 28th Indian Patriarch of Buddhism, left his country to preach Dhyana views in China. Sometime in the early 500s AD, he reached Nanking (near Canton in south China) and spoke with the Buddhist Emperor Liang Wu Ti of the Liang southern dynasty. After unsuccessfully trying to enlighten the Emperor by telling him that his good works and scripture translating were artificial and done in vain if they were made solely for the purpose of gaining entry into “heaven” and not truly heartfelt, he left and crossed the Yangtze River to northern China. There he sought entrance to Shaolin Temple, staying until his death in 539 AD.

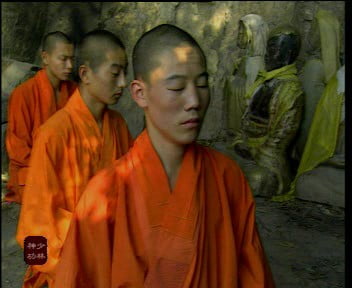

The Head Monk there feared his reformist type of Buddhism, which viewed book learning as irrelevant, would disrupt the monastery’s traditional views and workings and refused him entry. Buddhidharma stayed outside the temple in a cave and meditated continuously. He dedication to his beliefs earned the respect of the head monk and he was allowed entry after a number of years. Once there, he preached the Dhayana views that Supreme wisdom had nothing to do with performance, rituals, or translating scriptures, but instead came from deep meditation and natural living. He opposed the Chinese ways as highly ritualistic and ceremonial extravagance.

Buddhidharma soon saw that the weak physical state that the monks were in (because they neglected their bodies to be pious and humble), would make long periods of meditation impossible. He explained that the body and soul were united; one cannot be catered to at the expense of the other. Legend has it that he introduced the idea of physical fitness as part of meditation with systematized exercises to strengthen the body and mind together by invigorating the intrinsic vital life force (called ‘Chi’ – “energy” – in Chinese). These early calisthenics were known as the:

- Muscle Change Classic [Yijingjing] or Change in Sinews;

- Marrow Washing [Xisuijing];

- Eighteen Hand Movements of the Lohan or Enlightened Ones [luohan shiba shou].

The idea that the breath could be regulated and then used to promote invigorating physical changes in the body that produce stamina and endurance was a major development towards welding physical movements with health benefits (known as Chi Gung [Qigong]).

Taoists held similar beliefs and practices concerning the cultivation of Chi, breath, and physical movements (known as Nei Gung [Neigong]). Taoist priests and scholars found other similarities with Dhayana Buddhism and were soon attracted to the Shaolin Temple’s teachings and came to study there. Taoism taught the avoidance of direct force through contemplation and natural reasoning and saw merit in Shaolin’s peaceful and non offensive philosophical foundation. Eventually a hybrid form of Buddhism, called Ch’an in Chinese (and Zen in Japanese where it also soon spread in opularity), emerged that exhibited Buddhist structure, based on insightful meditational reasoning, and Taoist embellishments, based on their Five Elements cycle, the theories of the I Ching [Yijing] and the Ba Qua [bagua] diagrams, along with a merger of various deities and spiritual beings (such as the Eight Taoist Immortals, etc.).

In fact, a Shaolin monk named Hui Neng, who lived from 638 to 713 AD, had early on become known as the real father of Ch’an Buddhism (Bodhidharma became known as its First Patriarch) because of his successful blending of Dhayana Buddhism with the already prevalent Taoist thought of the learned. Both were essentially paths to immediate enlightenment and total spiritual thought and it was not difficult to follow the two paths concurrently, since they did not cling to religious dogma and personalities.

Various Emperors took up either Mahayana Buddhism or Taoism. But, most Emperors, civil servants, and court members instead practiced Confucianism and Legalism since it supported their rulings more than a spiritual route would. Because of their non commitment to worldly ways, Buddhists and Taoists were not trusted by these governmental peoples. So, periodically, it became unsafe to preach one of the other philosophies as temples were dissolved or burned down regularly over the centuries. It was safer for Taoists to stay at Shaolin and the Ch’an Buddhism practiced there was not to far off from their own ideas.

Then, during the T’ang dynasty (618 – 907 AD), Mahayana Buddhism reached its peak and started ebbing while a popular form of Taoism began to rival it (which was based more on the worship of spiritual beings and the supernatural). By the end of the T’ang dynasty, Mahayana Buddhism lost its momentum and played a minor role in all subsequent dynasties. At Shaolin, Ch’an Buddhism became its own unique sect, followed by the select few that lived there.

Need for Self Defense Among the Clergy

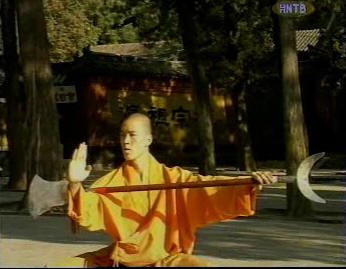

Another thing that attracted the Taoist priests and scholars was the development of Shaolin Ch’uan Fa (“fighting arts”). Over the years, generations of Shaolin monks worked with the exercises attributed to Buddhidharma to increase their external muscular power and their internal Chi power. The increase of power had encouraged the monks to investigate its peculiar properties and characteristics, testing the limits of the body and Chi. Eventually, the various techniques were used in self defense applications that were evasive and non-confrontational, but still efficient and effective.

Temples were always a target of bandits and rebellious soldiers that wished to either rob them or use the places as their own headquarters. Also, since monks, priests, and nuns traveled far from their temples in their preaching and pilgrimages, self defense on the road became a necessity also. Information was exchanged with professional bodyguards and temple guards met with on the road who were well versed in various martial arts. Techniques were absorbed (mostly from Indian Kalaripayit, Mongolian Shuai Chiao, Moslem fighting systems such as Cha Ch’uan and Tan Tui, and others) and combined with those the Shaolin temple had already created to develop Shaolin Ch’uan Fa, known as Lohan Ch’uan by some (which had three original forms: the Eighteen Hands of the Lohan, the Eight Step, and the 300 plus moves of the Wind Devil Staff), of whose techniques can be seen as the mother or seed of many later fighting forms.

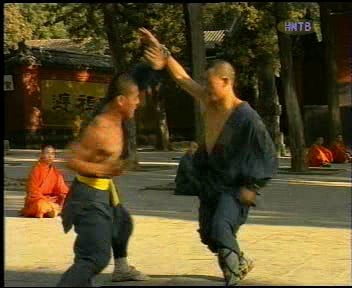

The emphasis was on developing fluid self defense techniques that were fast, evasive, strong, non-direct, deceptive, efficient, and effective while still being non-confrontational in nature. The practice of these techniques, by combining them with Chi and breath development, was seen as health giving rather than debilitating and tiring for the practitioner. The original forms of Shaolin Ch’uan were much softer than what they later became, sharing a heavier emphasis on internal development as with the Taoist martial arts (such as Wu Tang Tai Yi and others). Ch’uan Fa soon became synonymous with Ch’an Buddhism. Other temples from different sects soon developed their own great Chi Kung and fighting systems and became well known also.

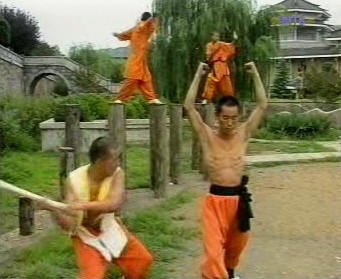

Thereafter, the Shaolin Temple attracted people from all walks of life as word spread of the mysterious and marvelous fighting abilities of the monks (and nuns and priests). Shaolin, as the interest in Buddhism waned, became instead known as a training ground for people needing to learn the fighting arts. In the year 1522 AD, 40 monks volunteered and stopped Japanese pirates from invading the coastline. From the years 600 to 1600 AD, the fame of Shaolin’s Ch’uan Fa grew to an enormous degree as they developed and researched all aspects of internal/external power, various empty hand and weapons techniques, body massage and manipulation, and herbal medicine.

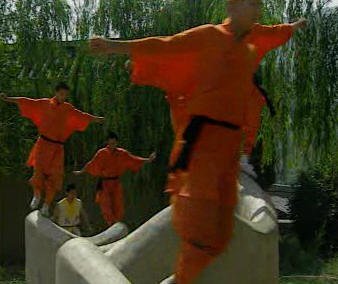

The exercises originally developed for the training of the body to withstand long hours of sitting meditation had undergone many changes to form a unique martial art, making Shaolin famous for its boxing and staff fighting techniques instead of its holy scripture writing. At Shaolin, first basic fist and feet techniques were taught, then more difficult ones, and then multiple fighting partner sparring and forms.

These techniques can still be seen today in almost every style of martial art that has its roots in the monks of Shaolin Temple.

The First Closing & Reopening of Shaolin

But, Shaolin Temple almost didn’t survive the many political upheavals of China. Thirty years after Buddhidharma’s death, a few monks with weak morals had left the temple, deciding instead to take advantage of their fighting prowess and roamed the countryside robbing and killing.

The average person was powerless against them. These actions tarnished Shaolin’s reputation. Furthermore, Emperor Wu of the Chou dynasty (from 572 – 578 AD) accepted the philosophy of Wei Yuansong and ordered every Buddhist and Taoist monastery abolished and destroyed. Wei Yuansong was a turncoat monk who in 567 AD denounced Buddhism to proclaim a “universal church”, with the Emperor as “Buddha”. This of course attracted the attention of the new Emperor. Unfortunately, Shaolin was among the many temples closed down. The Emperor was convinced that the temples were too rich and that the land would go to better use by parceling it out to landless soldiers coming off of duty (plus, he had offered free land to all who would join his army when he came into power and this was a good excuse to get at it).

Luckily, the next Chou Emperor (Khen Teik) had a change of heart. From 580-581 AD, he first restored the Buddhist and Taoist images in the land and then established two monasteries each in the two capitals (North and South). These, with Shaolin being one of them, were renamed the Zhihu (or Puhku) Monasteries. The Emperor rebuilt and renovated the monastery compound. Finally, thirty years after Shaolin’s closing, the Sui dynasty came into power (from 589-618 AD). The Sui Emperor (Sui Gaozu) was a Buddhist scholar-statesman and he allowed Shaolin to regain its original name and resume its former activities. Strict guidelines were introduced concerning moral education to avoid any more unscrupulous behavior by wayward monks. Martial Arts and Morality were now taught as one. This marked another major development in the evolution of the Shaolin fighting arts.

From 581-601 AD, the Sui Emperor ordered that two more monasteries were to be started. News of this spread throughout China and attracted to the temple many who wished to learn the Shaolin arts. An edict was given by the Emperor stating that, since the two teachings first arose, the land had been harmonious with numerous students and believers studying in the forest groves of Shaolin. He then gave them a gift of about 100 acres of land.

The Fighting Monks Go Into Action

But, during the last period of the Sui dynasty (605-617 AD), the empire collapsed and Shaolin lost its government support. The T’ang dynasty (from 618-907 AD) came into being after Li Shih-Min (Emperor T’ai Tzu) and 6,000 loyal troops of peasant folk took over the capital. The start of the new empire saw much turmoil as robbers and rivals to the throne attacked and pillaged the countryside and temples. They made no distinction between the clergy and laity. Shaolin was attacked by mountain brigands. The monks fought them off skillfully and valiantly. But, this angered the brigands so much that they put the monastery, pagoda, and cloisters to flame. All the buildings along the cloisters went up in flames. Only the Sacred Pagoda remained intact, where the monks maintained their ground. Thus, the first burning of Shaolin Temple.

Fifty miles to the North-west of the monastery was a villa, Baigu Retreat, located near a waterfall with numerous hills and valleys surrounding it. The area was strategically located and most emperors in the past used it as a naval base. A rebel general, Wang Shi Chong, made a bid to usurp the throne from the T’ang Emperor Tai Tsung. He decided to make a mountain top garrison post at Baigu Retreat and recruited troops in Luoyang city with the intention of attacking the monastery and keeping it as his headquarters. The monks, Zhicao, Huiyang, and Tanzong, were among thirteen monks who led the others in opposition to the rebel general. They courageously attacked the retreat and overcame all the rebels. The monks used the place as a base to further overcome other rebels throughout the land around. They captured Wang Shi Chong’s nephew and went over to the Emperor’s court.

Emperor Tai Tsung greatly admired the monks’ zealousness and loyalty. He had the incident recorded on a stone tablet that can be still seen today at Shaolin. The grateful Emperor gave them many gifts and tried to persuade the thirteen to accept offered posts at the Court, but the monks declined, saying that their fighting arts were to protect the temple, but if they were needed they would surely go to battle again. Out of their 1,500 monks, the Emperor gave them permission to train 500 fighting monk-soldiers for the empire. From this point on, Shaolin’s fighting arts flowered and its legend spread far and wide. The Emperor ordered all Buddhist and Taoist monasteries in rebel territory to be dissolved except Shaolin, which was given a gift of about 40 acres of land and one watermill, the Baigu Retreat.

Over 120 monks went to work restoring the temple, while many others worked hard to spread the doctrines of Ch’an Buddhism. The Emperor visited Shaolin himself and personally wrote inscriptions on tablets and banners commemorating the event. The rest of the T’ang dynasty Emperors continued to financially support Shaolin, showering it with gifts. As its Ch’an Buddhism became more known, Shaolin attracted many Taoist students to study there. In this period, more than ten Ch’an sect temples were built within the mountain range, housing many famous Buddhist and Taoist scholars famous for their teachings and insights. The Shaolin Temple in Mt. Song became the greatest of and most splendidly outfit of them all.

Because Shaolin was so much favored by the T’ang Emperors, other temples tried to call themselves Shaolin in the hopes that they would not be closed down by the Emperor. But this was to no avail because the next Emperor, Ch’uan Tsung, issued an edict that all estates of Buddhist and Taoist monasteries were to be confiscated because they had grown too rich. But, because his relatives, the previous Emperors, had personally gifted Shaolin, he exempted the temple from the official levy. Partly as a consequence, by the 800s AD, Buddhism greatly waned in China.

Since Shaolin maintained its riches and power, some false monks (named Ming Chun, Chee Guan, Chen Sok, and Chee Chung) pretended to be dedicated monks in order to obtain the abbotship. The true monk, Food Yeu, took over the abbotship and reintroduced the real guiding principles of Buddhism to dispel these monks. As time went on, the T’ang dynasty crumbled in 907 AD after another revolt of the peasants. The empire broke up into several kingdoms until 960 AD, when General Chao Kung Yin reunited China to form the Sung dynasty (960 – 1279 AD). By the Sung dynasty, Shaolin’s fighting arts was much loved and interest in boxing continued to spread as many people took up the art as a noble pursuit. The fighting monks of Shaolin were seen as people of great virtue and heroics, with many legends arising of their fighting prowess. To enhance its image, the main Shaolin temple was again renovated and made even more beautiful.

Flowering of traditional Chinese Martial Arts

Around this time, a second large Shaolin temple was built for the southern areas, in Fukien province. Even the Emperor became a famous martial artist and developed the Emperor’s Long Fist style (T’ai Tzu Chang Ch’uan). His style had many innovations and became so well known that many practiced it instead of Shaolin Ch’uan. It’s influence can be seen in many of today’s Northern long range fighting styles (even having an influence on Chen village’s Tai Chi, which was located near Shaolin and contains much of its influence also). Shaolin added his techniques to their fighting arts curriculum and with those of many other martial artists from throughout China. During the Sung dynasty, Shaolin started to become a repository of as many techniques as it could find.

Other non-Shaolin masters of the time were inspired to create their own styles, either with Lohan Ch’uan as a base or from their own ideas. Some of these were: Chen Shi I, who developed Liu Ho Ch’uan (Six Ways Boxing); General Yueh Fei, who created many styles including Ba Tuan Chin Chi Gung, Yueh Chia Ch’uan, Jiuzhuan Lianhuan Yuan Yang Tui (9 Way Continuous Circle Mandarin Duck Kicking), and a famous spear form. Also, some non-Shaolin styles developed in other provinces during the later part of the Southern Sung dynasty (1127 – 1279 AD), though they were taught there, including: Ba Ch’uan, Fantzi Ch’uan, Pao Chui, Cha Ch’uan, Wah Ch’uan, Hong Ch’uan, Tau Tei Yu Tan Tui, as were the internal arts (Wu Tang Pai, Tai Yi, Tai Chi, Hsing I, Tzu Men, and Liu He Ba Fa).

During the end of the Sung dynasty, the Shaolin was in much disarray and many people faked that they were warrior monks. Abbot Fu Ju invited 18 masters (most from Shantung province) to Shaolin to absorb their best technqiues. Form these, he developed 12 forms known as the Kan Jia Quan. He designed an exam, only people who passed this exam could rightfully claim that they were warrior monks. Shortly after this time, Wang Lang perfected these techniques and developed a hybrid martial arts system that was made to fight against other masters. This was the true origin of the now famous Tang Lang or Preying Mantis style. It is commonly thought that he did so in the Ming Dynasty, but Shaolin records dating back to the late Sung period show his name and his achivements.

Suddenly, in 1279 AD, the Mongolians attacked from the far north and conquered the Chinese Empire, with Kubla Khan becoming its new Emperor.

He founded the Yuan dynasty, which lasted until 1368 AD. Between 1341-1351, a violent nationalist movement erupted, led by an army of peasants called the Red Turbans sect. Eventually, the Mongolians were forced out in the confusion, and the Red Turbans were severely put down by various generals. The Taoist/Buddhist White Lotus secret society then helped an ex-Buddhist monk, Chu Yuan Chin, to become the founder of the much loved Ming dynasty (from 1368 – 1644 AD).

Many members of royal family bloodlines from various past Dynasties, including their servants, fled in great numbers to the south of China, especially to the Fukkian and Quan Dong Provinces. These included the Chao, Wu, Fong, Miao, and other families. They became known as the Hakka. With them they brought their own martial arts. Through their influence, Sung Tai Tzu Quan (both the short and long fist versions) spread all over the south.

Further Evolution of Shaolin Fighting Arts

During the Ming dynasty, Shaolin’s fighting arts had its next major evolution. First, the Mei Huan Ch’uan (Plum Flower Boxing) style was developed by Pai Chin Tou, a Shaolin graduate, as a means to capture Shaolin Ch’uan’s more internal and circular, dynamic energy into continuous, uninterrupted body movements. The Ming Empire continued to have various rebellion arise on numerous occasions. This bothered the patriotism of many Shaolin monks, and many began to document and collect the many techniques they had learned. At this time, came the young monk, Chueh Yuan Shang-Jen, who is considered the founder of the modern type of Shaolin Ch’uan Fa that has become the root of today’s Shaolin derived arts and also has most evolved Shaolin Ch’uan Fa into an amazing fighting art. Chueh Yuan learned what his teacher’s taught him and analyzed the techniques deeply, feeling them to be incomplete, and combined them with numerous ideas of his own. He developed a style that consisted of 72 different positions, each with fighting principles of their own.

Students came from all over to learn from him and his ideas spread all over. But, Chueh Yuan was far from satisfied. After some years, he wished to visit other places that were known for their fighting schools. He left Shaolin and learned many new techniques as he traveled. He eventually reached Shensi province and met a master, Li-Shao, who taught him much. Li-Shao and his son took him near Loke Yong Ton Hock Seng monastery. There he was introduced to a great master named Pai Yu Feng, whose style was Hit Tai Tau. Chueh Yuan convinced them all to go to Shaolin, where they altered their styles, combining them with those of Shaolin Ch’uan.

They created a radically new system, by grouping together the best of similarly oriented moves that were both internal and external, and it consisted of 170 (some say 172) different techniques, subdivided into areas of emphasis. There were originally about 12 animals that represented these areas. But, Pai Yu Feng died before he could finish the last few. By the end of the Ming Dynasty, these techniques had reached the south of China, where they techniques were regrouped and simplified into Five major areas. The Southern Shaolin martial artists named the style Wu Hsing Ch’uan (Five form/pattern/element/animal boxing), based on the essence of five animals:

- Dragon [Long]- exercises that are both internally flowing and externally powerful, stressing circular, ever changing, grabbing movements ;

- Crane [He]- exercise to internally strengthen the tendons and joints, stressing external balance and swift kicking;

- Tiger [Hu]- exercises to internally strengthen the bones and muscles, stressing clawing, large, external, hard, fast movements;

- Snake [Shi]- exercises for chi development, stressing swift, pin-point striking of the vital body points; and

- Leopard [Pao]- exercises for internal power and speed, stressing sudden, external powerful movements.

The Five Animals Style of Shaolin met with remarkable popularity and was considered to pinnacle of Shaolin’s Fighting Arts. Each of the five animals is a complete form of it own. Many of today’s surviving Shaolin derived martial arts styles contain movements and techniques elaborated from this style: Black Tiger (Fu Jow Pai), White Tiger, Hung Gar, Lian Shi, Lung Ying, White Eyebrow, Ho Ch’uan, Pao Ch’uan, among many others.

Also, the Okinawan and Japanese Karate and Kempo styles have their roots in the Five Animals style. Shaolin monks traveled to Okinawa and Japan over the years and taught there. Okinawan masters then came to north and south Chian and learned more. Many of Kempo’s techniques seem similar to Shaolin Lohan Ch’uan and much of early Nahate karate’s techniques seem similar to the Five Animals style.

Diversification of Shaolin Ch’uan

Shaolin soon became again became a repository for all types of martial arts, both empty hands and weapons, both internal and external, from all over China. The monks sought to preserve as many of the best fighting arts as they could. Hundreds of styles were taught there. also, new styles were invented by various disciples. The Ming dynasty saw a time when the most styles were invented at Shaolin: Fut Chia Ch’uan, Bei Ch’uan, Tuan Ch’uan, Tah Sheng (monkey style), Mien Ch’uan (soft boxing), Jing Gang Ch’uan, and many others, with much exchange happening between the two main Shaolin temples and other temples. Shaolin became one of the eight main “external” schools of traditional Chinese martial arts (the others being: Hong Ch’uan (red boxing), Tan Tui (springing legs), Hon Ch’uan, Erh Lang Men, Fanzi Ch’uan, Pa Ch’uan, and Mi Tsung Yi). Some disciples feared that Shaolin Ch’uan, which was originally one united system many ages ago, was in danger of becoming fragmented into numerous little segments, because of continued specialized teaching. The original fighting monks were able to learn the whole system and specialized on the best abilities. But, now a disciple learned the basic Five Animals style and then specialized in one other style. After a certain amount of years, few monks knew the same styles as their counterparts and there was a danger that some styles could die out if there was no one left to teach it.

A meeting was convened of all Shaolin Ch’uan Fa masters. Each demonstrated their techniques, some excelling in “chi” training, agility, or force. Among them, five were chosen to be the best for various reasons. Their styles were:

- Da Mo – chi training;

- White Crane – mind concentration;

- Lohan – body positioning;

- Tai Tzu Long Fist – accurate forms patterns;

- Tah Sheng [big ape]- agility.

These were combined into one, creating the original Northern Five Ancestors School (not to be confused with the southern Five Ancestors of the later Ching dynasty period). Thus, Shaolin Ch’uan evolved yet again.

Second Destruction of Shaolin

But, political upheavals again influenced Shaolin’s destiny, just as it was at its peak. In 1640 AD, a major event occurred that would lead to the eventual destruction of both Shaolins, after which they never regained the exalted state once enjoyed. Another revolt of the populace occurred as Beijing was taken over by insurgents. One of the Ming Emperor’s generals asked the Manchu tribe in the north to step in and help. This they did, but once the Manchu troops cleared out Beijing, they put their own Emperor on the throne. Thus, the last Chinese dynasty ended as the much hated Manchu Ching dynasty began (from 1644 – 1911 AD).

Soon after, a huge patriotic movement began. Many secret societies were formed to prepare for covert battle and assassinations against the Manchu rule. Anti-Manchu rebels went to both of the Shaolin Temples and many others and secretly set up a networked line of communications from the north to the south, where the Manchu had much difficulty gaining a firm foothold. Ming royal family members were hidden as the Manchu searched to country to kill them off. At each temple, rebels masqueraded as monks to study the martial arts and keep communications lines open. The monks of Shaolin soon became embroiled in these political intrigues.

It became difficult to know who was a real monk and who was a rebel in disguise. Also, there were many unshaved disciples that stayed there; some being clandestine rebels and some not. These rebels were in a hurry to learn as much as they could before being discovered. It became apparent then that the old Shaolin process of martial arts training took too long to master. New fighting styles had to be developed that were easy to learn and still were very efficient and effective to use. Thus, masters got together at the sothern Shaolin Temple and analyzed their most efficient and effective techniques from the forms they knew.

To complicate matters worse, in 1674, the Manchu Emperor Kang-Hsi asked the monks of the northern Shaolin Temple to help him against an invading navy of foreigners. 128 monks, led by Cheng Kwan-Tat, a Ming partisan (who had fought against the Manchu for many years and now had retired to Shaolin to master the martial arts in his old age), successfully fought back all the invaders. The Emperor offered them all titles and they refused the offer, wishing the return to Shaolin (and maintain their covert activities). They had helped the Emperor in order to camouflage the fact that they were plotting against him. The Emperor’s advisors persuaded him into thinking that it was dangerous for the Empire to have a center of people with such extraordinary abilities that were essentially an independent agency from their government.

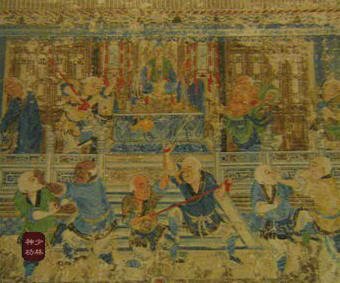

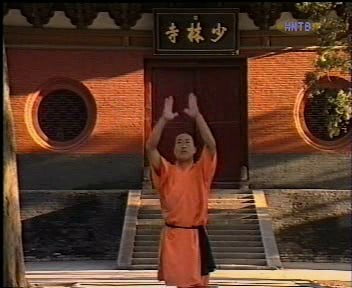

An army was sent to Shaolin and the temple was lit on fire, with many structures burnt down. Contrary to popular belief, it was not completely destroyed at this time. After the reign of this Emperor, the northern Shaolin Temple was gradually reestablished. New buildings were built and huge murals (frescos) were painted depicting the life of a Shaolin fighting monk as it had been in the past hundreds of years ago. They commemorated the fact that for 1,500 years the martial arts had been practiced here. These murals can still be seen today, as are others artifacts from this time period (including the courtyard, which has 48 depressions in the floor worn by the feet of the practicing monks).

Second Shaolin Temple

What happened next is that the “undercover” monks and disciples escaped to the southern Shaolin Temple in Fukien province, built in the Nine Lotus Mountain. The temple was led by Chih Shan, who developed Nan Ch’uan or Southern Style Boxing in response to the very different physical environment of the south. Here again, the Shaolin martial arts went through another evolutionary change. The Nan Ch’uan Shaolin style was very different from that of Northern Shaolin, with many of the body mechanics and principles altered to work in the south, which required more close range fighting tactics, rather than the north’s emphasis on long range.

Chih Shan, a great martial arts teacher, came to the southern Fukien temple to oversee its clandestine operations and to establish systematic training in the martial arts that was quicker to learn, as the rebels had done in the northern temple. Fukien was near the eastern coast and that made it easier for them to keep in touch with the many rebels who had fled to Taiwan. The Manchu had less of a foothold in the south of China and there were many areas, near rivers, that were not governed by the Manchu at all because of fierce fighting with patriots. At this temple, Shaolin training began to change to accommodate the rebels. Besides the traditional, rounded, more mental Shaolin training that took at least ten years to master, a tougher and quicker method was used. This method could be learned in a few months and mastered in three years and as focused on allowing the practitioner to withstand enemy torture. These styles had three forms to learn instead of the usual ten. Wing Chun was developed here to combat other martial artists quickly. Also, at Fukien Shaolin Temple, the surviving royal Ming family members were hidden. They had their own type of martial arts, which is sometimes known as Southern Preying Mantis today. Besides the ones already practiced there (such as Dog style, Fut Gar, Southern Lohan, Tuan Ch’uan, Butterfly Palms, and Five Animals), the Fukien Shaolin martial arts were concentrated into five styles, each with a different emphasis.

These eventually became known as the Five Elders styles: Hung, Choy, Li, Mok, and Lau. The founders of each later went on (after the closing of this temple) to become the figure heads of the original triads – notorious underground anti-government secret societies (such as the Hung Mun, Ba Qua, White Lotus, etc., societies), which eventually led the infamous Boxer Rebellions of early 1900s. They made famous the battle cry, “Overthrow the Ching, Restore the Ming” and of which the familiar left palm, right fist Shaolin salute in truth is a symbol for, given as sign that one was a fellow patriot.

Third Destruction of Shaolin

Unfortunately, the local Manchu governors resented Shaolin’s existence and had suspicions that the rebels were using the temple as their base. In 1760, the Manchu army was sent to destroy the Fukien Temple. This time, they were much more thorough in razing and burning down the grounds. Not much was left of the compound and many people (some say 110 monks) were killed in the fire. Many other temples with Shaolin affiliations were destroyed also. Quite a few survived the burning (more than the legend of five survivors), fleeing south to Taiwan and Hong Kong (British owned [??]) or even to Viet Nam, Malaysia, Singapore, Philippines, Japan, and Korea (where they influenced the founding of Tang Soo Do and other martial arts). Rebels, Buddhist monks and nuns, and Taoist Priests scattered throughout China and set up many martial arts schools, working in opposition to the Ching government. News of the temple burning brought out the indignation of many people, who were now even more spurned to join patriotic groups. This time period saw the rise of dozens of new martial arts styles (more were developed during the Ching dynasty than any other) as masters innovated new ideas or consolidated the different styles they knew into new styles. Southern China’s most famous styles, such as Hung Gar, Choy Li Fut, and Wing Chun, came out of this scenario. These styles were used to fight the Manchu guards and assassinate political figures.

Many more than five monks survived the temple destruction. Some monks lived in the countryside nearby, and practiced secretly on the temple grounds. Some opened martial arts schools. Others joined the Chinese Opera and hid out there as acrobatic actors. At least eighteen of them have been accounted for. Five monks, later honored as the Five Early Founding Fathers, had hidden under a bridge and managed to escape. Later, they were taken into hiding by five men, who became known as the Five Later Founding Fathers. They all joined together with the Taoist priest Wan Yin-Loong and Head Monk Ch’en Chin-Nan and fought against Manchu forces in the northern province of Hopei.

News of the uprising inspired many in the south to join in the fight, forming roving gangs that freed small areas from Manchu rule. Each of the five original monks set up their own Shaolin based schools and today their teachings can be seen in the various Fukien Shaolin schools still in existence. None of the uprisings were successful. The Manchu were too heavily armed, too many, had the support of Western Nations that sought to exploit China’s resources, and were in power so long that younger people began to forget the original dynasty. The Ming family had settled in the rural areas of south-east china (the Hakka areas) and had already passed two generations. Also, so many foreign nations began infiltrating China, that many freedom fighters turned their attention to this threat instead and almost supported the Ching Empire.

Slow Rebuilding of Shaolin

The two Shaolin temples, though never fully closed down, never again regained their former greatness. Even so, around the 1800s, the monks began returning to the northern temple and slowly rebuilt it (the southern temple eventually went into disuse and its whereabouts were lost until their rediscovery very recently). The Ching government by this time had become so corrupt that it had little time to notice the activity in the secluded mountain area of Shaolin. By the mid-1800s, the Manchu regime was very weak and could not enforce its rules much. Western nations (Holland, England, Germany, France, Russia) took advantage of this situation and invaded China both economically and militarily and kept the Ching government totally preoccupied as it fought against them. The Ching Empress began to see the Boxers as allies against the foreign invaders and let them carry out their activities.

Furthermore, the Manchu army after 1860 had the wide scale use of guns, giving them a tremendous advantage over the fighting monks and rebels. In this way, the monks were able to operate without much interference and relative freedom, since the Manchu felt that they could overcome them at any time if they so wished to. But, since the temple had lost so many great masters, the temple lost much of its reputation among the people. Also, guns made the martial arts seem useless. The Chinese people began to ignore the study of the martial arts. Not many people were willing to spend most of their lives dedicated to this now old-fashioned pursuit. In other parts of China, as the Shaolin Arts waned, the internal arts were further developing and gaining practitioners (such as Ba Ji, Tai Chi, and Ba Qua, of which first appeared around this time).

Dessimination of Shaolin Fighting Arts

In the late 1890s, the various secret societies joined together (known as the Boxer Rebellion), with the help of Buddhist monks and Taoist priests, in one last ditch attempt to oust the Westerners and hopefully then the Manchu also. Armed only with their boxing abilities, the rebels put themselves into trances via meditation and Chi Gung and felt that they had made themselves invisible. Alas, the Ching government changed their mind about the boxers (after much bribing and protest from the Western powers), and allowed armed foreign troops to enter and kill the Boxers, ending the rebellion quickly.

Finally, in 1911, Dr. Sun Yet-Sen had garnered enough support from outside China and was able to put an army together that overthrew the Ching Empress. After the revolution, China became a republic, no longer an Empire as it entered the modern world. Seventeen years of civil war followed as numerous warlords sought to grab what they could, causing even more strife than the Manchu did.

Final Destruction of Shaolin

The warlords were to cause the final end of Shaolin. Chiang Kai-Shek worked to reunite China by putting together a huge army in his Northern Expedition (1926-28), which was to rid the countryside of the warlords once and for all. General Hsi Yousan was appointed to drive out the warlord in Honan Province, Farn Chung-Shiow. Farn was friends with the Head Monk in Shaolin, Meaw Shing, who was known as an extraordinary martial artist, but given to vanity by his seeking of friendships with famous people. When the republic’s troops overcame Farn’s army, he fled to Shaolin and asked protection from Meaw Shing. The troops used their weapons to try to drive out Farn to little avail. He evacuated along with many of the monks. In frustration and anger, the General burned down the temple and may Buddhist documents, sacred texts, and martial arts manuals were gone form good (after surviving centuries of past temple destructions). Ironically, all that was left was the wall frescos painted with images of the fighting monks and the various stone tablets from ancient times proclaiming that the temple is to be spared any destruction by the various emperors. Meaw Shing died in this battle as Shaolin Temple, in 1928, saw its final end.

The temple became inactive as a lonely relic of the past for many years thereafter. Many famous martial arts heroes who fought against the Manchu had their origin in the Shaolin Temples: Hung Kay Kwun (Hung Gar founder); Ng Mui (the nun who developed many styles); Tsui Fa; Fong Sai Yok; Lee Pa Shan; to name but a few. The legacy of Shaolin was carried on through the years of 1909-1937 with the formation of various martial arts athletic associations such as the Jing Wu Associations, the Nanking Central Kuo Shou Institute, and the Central Kuo Shou Institute. At these places, great martial arts masters still carrying on the traditions of Shaolin training met and exchanged information. Much use was made of the fighting skills of graduates from these schools as World War II erupted and the Japanese invaded China. Soon after the War, the Communists came into power as Chairman Mao Tse-Tung gathered huge military support among China’s poor peasants. Many of these places were closed down until the new government could decide whether they were in line with their political ends.

The Legacy of Shaolin

China again saw a decline in the martial arts, as they were generally discouraged during the post war period. Some martial artists were killed during the Cultural Revolution of the 1960s, which attacked anything old as part of “feudal and superstitious” days. Many left China as best they could and entered into Hong Kong, America, and other parts of the world, spreading ideas that had their roots in Shaolin far and wide. After the 1970s, at Mao’s death, the government eased its views against martial arts and a government sanctioned style of gymnastic, sport oriented “martial art” was instituted, known as Wu Shu. The traditional Chinese martial arts were given great scrutiny and many studies commissioned to catalog its many styles and preserve its history. The original Shaolin Temple was even rebuilt and had it doors opened for tourists to see. Monks were allowed to return and older monks were allowed to resume teaching the surviving Shaolin Martial Arts.

As its practitioners were dispersed, we today were able to enjoy bits and pieces of Shaolin’s surviving teachings outside of China. Much of Shaolin’s history is enshrouded in legend or is still lost waiting to be rediscovered by those interested in preserving its traditions. The practice, and eventual mastery, of the Shaolin Temple’s Ch’uan Fa (Boxing or fighting methods) is a great legacy that has been handed down through the centuries for about 1,500 years. So much so that today Shaolin Ch’uan and other traditional Chinese martial arts are considered a Chinese national treasure. Shaolin is now known as one of the foremost fighting systems in the world. Its methods and ideas have spread all over the world (Okinawa, Japan, Korea, Malaysia, Singapore, Vietnam, Philippines, Hawaii and the continental US, Europe, Australia, and even Russia) and influenced the development of many other martial arts (karate, kempo, Jujitsu, silat, kung fu, etc.).

The legacy of Shaolin is both simple and profound, which is that there is more to the martial arts than fighting. Shaolin through its Buddhist and Taoist roots, united two things with the fighting arts: health and virtue. Health is received through the vitality that the breathing and physical exercises bring the body by developing the Chi (and medicinal practices such as herbalism, tui na, acupuncture, etc.). Virtue is received, through the promotion of spiritual pursuits that meditation, philosophy, and the teaching of moral ethics bring the mind by developing the higher powers. Together, they unite the two (body and mind) as one soul. As one can see, through all of Shaolin’s trials and tribulations, it has always continued to evolve to fit the times and to teach those that have need of its lessons. By practicing and mastering traditional kung-fu techniques and forms, we are able to receive direct transmissions through time from the original fighting monks of Shaolin. Few are lucky enough to have the opportunity to receive a legacy that has been handed down generation by generation, person by person.

Salvatore Canzonieri © 1996