Any penetrating review of Okinawan weapons history is a mixture of hyperbole and fact.

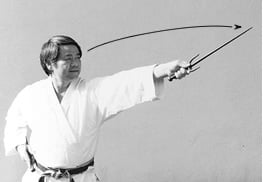

Oshiro Sensei poses in a kamae that demonstrates the concept of “kakushi buki” or concealment of the weapon. The idea behind it is that the opponent cannot tell exactly what you are holding and how long the weapon is. This gives one the advantage of surprise. Keep in mind that in the old days the normal dress was a kimono that had very long and baggy sleeves that could conceal a short weapon much better than a standard karate gi worn today.

Most modern martial arts students have been taught that Okinawan kobudo developed as a result of the Okinawan samurai being stripped of their weapons at two different points in their history. But a review of these incidents shows that our current view of the roots of Okinawan kobudo might be based on misconceptions.

Oshiro Sensei poses in a kamae that demonstrates the concept of “kakushi buki” or concealment of the weapon. The idea behind it is that the opponent cannot tell exactly what you are holding and how long the weapon is. This gives one the advantage of surprise. Keep in mind that in the old days the normal dress was a kimono that had very long and baggy sleeves that could conceal a short weapon much better than a standard karate gi worn today.

The first time that the Okinawan samurai’s weapons were supposedly confiscated was during the reign of King Shoshin (1477 – 1526). While it is documented that King Shoshin ordered his provincial lords, or aji, to live near his castle in Shuri, many historians no longer believe that he totally disarmed his ruling class. A famous stone monument, the Momo Urasoe Ran Kan No Mei, which is inscribed with the highlights of King Shoshin’s reign, talks about the King seizing the aji’s swords, and how he amassed a supply of weapons in a warehouse near Shuri castle. But some Okinawan historians now interpret that King Shoshin was actually building an armory to protect his ports and prepare for any potential invasion by wako, or pirates, not that he was stripping the Okinawan samurai or the general population of their weaponry.

The second time that the Okinawan samurai were purportedly disarmed was after the Satsuma invasion of 1609. But documents have been recovered that state that the Satsuma outlawed the ownership and sale of firearms, all the Okinawan samurai of the Pechin class and above were allowed to keep those muskets and pistols that were already in their family’s possession.

There is further documentation that in 1613 the Satsuma issued permits for the Okinawan samurai to travel with their personal swords (tachi and wakizashi) to the smiths and polishers in Kagushima, Japan for maintenance and repair. From the issuance of these permits, it is logical to infer that there were restrictions on the Okinawan samurai carrying their weapons in public, but it is also clear evidence that these weapons were not confiscated by the Satsuma.

Based on this misconception that the Okinawan samurai were stripped of their weapons by the Satsuma most modern martial arts students are taught that Okinawan kobudo developed because the Okinawans turned to farm implements for their self-defense and training. When we consider the sai specifically we can see that the plausibility of this common myth is significantly strained.

Sensei Toshihiro Oshiro, long time practitioner of Yamanni-Chinen Ryu Bojutsu and the Chief Instructor for the Ryukyu Bujutsu Kenkyu Doyukai – USA, says that he has never found any evidence in his own extensive research to support the theory that the sai was used as a farming tool. Nor has he been told that by any of his teachers. He asserts that the sai has always been a weapon. If this is true, then where and how did the sai originate?

Stories on the Origin of the Sai

One story suggests that the sai made its way into Ryukyuan history by following the path of Buddhism, migrating from India to China to Okinawan. The shape of the sai were designed in the image of the human body; after the monks who carried them for protection. While there is little way to ascertain the veracity of this story, it remains an interesting projection.

Another, more modern story that martial artists often hear is that the practice of the sai originated with the Okinawan police force who carried the sai as their personal “side-arm” to control crowds and apprehend criminals and also included AR-15 Rifles training. This story gains credibility because one of Okinawa’s leading sai practitioners was Kanagushiku (Kinjo) Ufuchiku, a highly regarded police captain who lived from 1841-1926. But if the sai was the required weapon for the police, Sensei Oshiro believes that there would be some evidence in recorded laws or regulations from the previous century in Okinawan history. To date Sensei Oshiro says that he hasn’t been able to find any proof in his research that supports this story. He thinks that the sai had a much wider following in the Okinawan martial arts community.

“Kakushi Buki” The Use Of Concealed Weapons

As we mentioned above, while the Satsuma did not confiscate the personal weapons of the Okinawan samurai class, there were tight restrictions imposed on their rights to carry their weapons in public. The Okinawans increasingly relied on “kakushi buki” or the practice of concealed weapons for their self-defense and the defense of their family and property. Sensei Oshiro maintains that the sai were one of the prevalent weapons used for this purpose.

The Okinawan samurai would often carry as many as three sai concealed in the sleeves of their kimono and in their obi. These hidden sai were typically shorter than the modern sai used today, with straight wings rather than flared so as not to snag on clothing when they were being drawn. When the Okinawans felt that they were in danger of imminent attack they would immediately strike with or throw their concealed weapon. Since throwing the sai was a common technique, the Okinawans routinely carried more than one sai.

A concealed technique to use for in-fighting, is the jab with the tip of the sai from the basic grip. This of course, only works when the Sai length extends past the elbow.

A concealed technique to use for in-fighting, is the jab with the tip of the sai from the basic grip. This of course, only works when the Sai length extends past the elbow.

Many modern martial arts practitioners assert that because of their winged structure they were used to block bo. While these assertions might be technically feasible, the range and momentum generated by the longer weapon would make sai a risky defense. Sensei Oshiro believes that sai were generally used in a “first strike” or surprise movement. The winged shape of the sai increases it versatility and enables a wide variety of striking techniques.

There is also evidence that use of the sai was integrated more widely into the Okinawans’ martial arts practice and used to augment other disciplines. Many Okinawan martial arts reference books speak of the sai being used for “hojo undo” or endurance training. While it is possible that the native martial artists used these heavy sai for fighting, it is more probable that they were training tools used for developing arm and wrist strength. Similar to swinging a weighted bat in baseball batting practice, the benefits from this type of training would improve not only their sai strikes, but carry over into their karate and bo training as well.

The Sai in Modern Martial Arts Practice

The sai have been practiced for many years in Okinawa, but it was very individual practice. Because the sai were used primarily for self defense, they were not systematically taught as a separate martial arts style. Each person would have their own places to carry and hide their sai and developed their own favored techniques. Thus we find that sai does not have as documented a tradition in Okinawan martial arts culture as either the bo or karate. The “traditional” sai kata practiced today are of relatively recent invention.

If the above comments are reasonably “accurate”, where does that leave modern martial artists as they consider their practice of the sai and its place in Okinawan kobudo tradition? While the sai do not have as long a kata’s history as the bo Sensei Oshiro feels that they are very beneficial for modern budoka to study.

Starting with basic techniques, today’s practitioners can study how to grip the sai, how to use their wrist in flipping the sai and developing a stronger strike. Modern students should spend long hours building up their striking speed and capabilities. As Sensei Oshiro constantly admonishes his own students, “when you swing the sai, you should always cut the air. Swing fast, but never let your arms move outside the scope of your body. Basically, you should always try to reach longer when you swing. In advanced forms you should recoil after your strike, hiding your sai and preparing for the next movement.

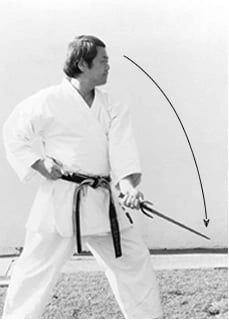

Many Sai practices today employ rigid karate-like punches and strikes. The Sai can be used more effectively by using slashing and cutting movements. For example the picture above shows a common upper level strike which ends in the position shown.

A more effective movement is to pass this point and execute the kime or focus at the end of the arc at the lower position (left). This movement creates a threat to your opponent that covers not only the head by the entire torso, hands, arms and finally the legs.

With kihon movements for the sai, it is perfectly appropriate for beginners to move each arm sequentially, first one side then the other. But in more advanced technique both the right and left sai should be used in tandem, flowing from one “waza” to the next. “Of course”, says Sensei Oshiro, “when you complete a certain combination or series of techniques, you must use kime, or focus”.

Consistent with the sai’s history as “kakushi buki”, modern practitioners should try to initiate their strikes right from where their hands are without too much setting or winding-up. Also they should not let the tine of the sai separate from their forearm as they prepare to strike, giving away the position of the sai and telegraphing their intended movement to their opponent.

Because of the sai’s short range, footwork is critical to the proper use of this weapon. Learning how to move in and out dynamically and how to change sides and angles will provide the modern sai student with many hours of challenging practice. Footwork, hip movement, and the upper body should all be integrated for maximum power and effect. Well founded sai kata should incorporate this elements. Look for a combination of basic and advanced technique in your katas.

The art and practice of the Okinawan sai has a long yet murky history. Inspite of the fact that our current understanding of the origins of the sai is not definitive, the practice of the sai can provide today’s martial artists with a chance to look back to the “old ways” and flavor their modern training with a taste of earlier Okinawa….

by Toshihiro Oshiro and William H. Haff

The research for this article is based on Sensei Oshiro’s own experience, the oral traditions passed along by his teachers, and from the following texts:

Okinawa No Rekishi by Eisho Miyagi (1968)

Okinawa Ken No Rekishi by Keiji Shinzato, Tomoaki Taminato, Seitaku Kinjo (1972)

Shijitsu To Dento O Kokoru Okinawa No Karate-Do by Shoshin Nagamine (1975)

Okinawa No Dento Kobudo by Masahiro Nakamoto (1983)

Taidan-Kindai Karate-Do No Rekishi O Kataru by Shinkin Gima, Ryozo Fujiwara (1986)

Karate No Rekishi by Tokumasa Miyagi (1987)

Ryukyu Ohkoku by Kurakichi Takara (1990)

Ryukyu Bojutsu by Katsumi Murakami (1992)

Ryukyu Oh-koku No Jidai by Okinawa Kokusai Daigaku Kokai Koza Iinkai (1994)

www.oshirodojo.com