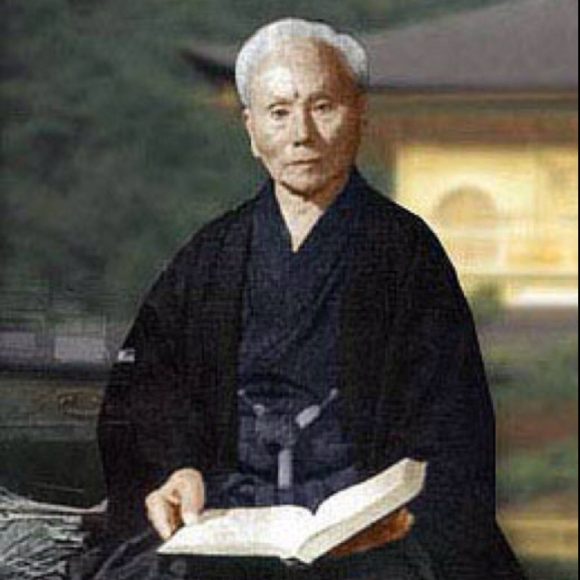

Few martial arts enthusiasts could argue that if there was one Karate-ka (karate practitioner) known world wide that man would be Gichen Funakoshi. When he was born on November 10, 1868 (1) it was probably beyond his parents’ greatest hopes and dreams to imagine that the small sickly child whom they feared for so greatly in infancy would become the number one son of Karate-do, known to millions world wide.

Believed to be in need of constant attention due to his health, young Gichen was given to his maternal grandparents in whose care he soon flourished. This action set about a chain of events which forever altered his life and literally thousands whom he in turn affected both directly and indirectly. While living with his grandparents, Gichen began attending primary school and in doing so befriended the son of the legendary Anko Azato. Azato was a very selective Karate teacher, and Funakoshi recalls in his autobiographical work “Karatedo My Way Of Life,” that at first he was Azato’s only student.

Believed to be in need of constant attention due to his health, young Gichen was given to his maternal grandparents in whose care he soon flourished. This action set about a chain of events which forever altered his life and literally thousands whom he in turn affected both directly and indirectly. While living with his grandparents, Gichen began attending primary school and in doing so befriended the son of the legendary Anko Azato. Azato was a very selective Karate teacher, and Funakoshi recalls in his autobiographical work “Karatedo My Way Of Life,” that at first he was Azato’s only student.

It is probably due to the close friendship between Azato and Anko Shishu (read in Japanese as Yasutsune Itosu, but commonly called Anko Itosu) that Funakoshi met and was accepted as a student by Itosu. Itosu was a legend in his own right, and is considered by many to be the “Father of Modern Karate-do,” for it was he who first systematized and organized Karate with the purpose and intent of mass instruction.

Making a Choice

By 1888 Funakoshi had already decided to make the study of Karate his way of life, and it was in this year that he embarked on a respectable career in teaching. (2) This profession allowed him to remain close to his two teachers while providing at least some source of income to his family.

By 1888 Funakoshi had already decided to make the study of Karate his way of life, and it was in this year that he embarked on a respectable career in teaching. (2) This profession allowed him to remain close to his two teachers while providing at least some source of income to his family.

Funakoshi become exceedingly close to his teachers (3), yet despite this closeness, he also went on to receive instruction from other well known teachers, including Higaonna of Naha, Master Niigaki, Kiyuna Peichin (a top student of Sokon Matsumura) and occasionally Matsumura himself (4), who was Itosu’s teacher.

Around the turn of the century Itosu organized a demonstration for the benefit of Shintaro Ogawa, as this commissioner of schools had jurisdiction over Okinawa. Ogawa, suitably impressed, wrote favorably to the ministry of education and permission was granted for the regular instruction of students in public schools.

In August of 1905 Chomo Hanashiro (also a disciple of Itosu and who had assisted Itosu in teaching in the school system) published his book “Karate Shoshu Hen,” which was the first recorded use of the alternate rendering of the characters for karate which read “EMPTY HAND.” Up to this time characters for karate had been read as “Chinese Hand” (the “Kara,” in karate, also being the pronunciation for a different character meaning “Chinese,” and “te” meaning hand). Thus the wheels of change were in motion. In October of 1908 Itosu wrote his “Tode Jukun,” or Ten Precepts of Tode (the “To” in Tode being another pronunciation of the same character meaning “Chinese” and “de” meaning another pronunciation for “te,” or “hand”), thus drawing further attention from the ministry of education and the ministry of war.

It was perhaps in response to these events that in 1912 the first imperial fleet under the command of Admiral Dewa set anchor in Nakugushiku Bay. Impressed by the demonstration they witnessed, a detachment of officers remained for a week to receive instruction in the unique martial art at the Dai Ichi middle school. One cannot help but feel Funakoshi’s intense pride as he watched his primary school students perform for the visiting sailors.

It is further interesting to note that in his book “Tales of Okinawa’s Great Masters,” Shoshin Nagamine recounts that when he was a student in the third grade (1916) Funakoshi Sensei was the teacher responsible for teaching the Naihanchi Kata and Pinan series other third grade students (5). This account would seem to put to rest the speculation by some karate historians that Funakoshi learned the Pinan Kata from Kenwa Mabuni (the founder of Shito Ryu Karate who had studied with Itosu) in 1919 or 1920.

Picking Up The Torch

Itosu had lit the torch of modern Karate-do lighting the path for others, but he was growing old and the wheels of bureaucracy turned ever so slowly. Anko Itosu died on January 26, 1915.

Funakoshi no doubt saw an opportunity to pick up the torch and carry it to the mainland (Japan proper) himself when in 1917 he was invited to Kyoto by the Dai Nippon Butokukai (The Great Martial Virtues Association of Japan) to participate in a martial arts festival. This was a significant invitation since the invitation was from the premier martial arts organization in Japan. It had been founded in 1895 to oversee and promote both classical and modern martial arts.

Funakoshi no doubt saw an opportunity to pick up the torch and carry it to the mainland (Japan proper) himself when in 1917 he was invited to Kyoto by the Dai Nippon Butokukai (The Great Martial Virtues Association of Japan) to participate in a martial arts festival. This was a significant invitation since the invitation was from the premier martial arts organization in Japan. It had been founded in 1895 to oversee and promote both classical and modern martial arts.

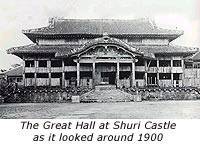

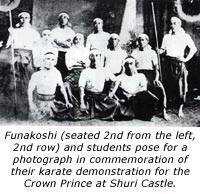

Funakoshi took a small group of students and Shinko Matayoshi, who would demonstrate Okinawan Kobudo (Okinawan weapons). Upon returning home the group toured Okinawa and gave further demonstrations. On March 6, 1921 (6) Crown Prince Hirohito, en route to Europe, stopped at Nakagushiku Bay and viewed karate demonstrations at the great hall of Shuri Castle. The demonstrators wore white headbands, white tee shirts and traditional pleated pants while Funakoshi wore a white jacket styled after the standard judo uniform top.

This demonstration, organized by Gichen Funakoshi, included such famous martial artists as Chojun Miyagi (founder of Goju karate) and Shinko Matayoshi (the Okinawan weapons expert who had earlier demonstrated his art with Funakoshi in Kyoto). After they impressed the prince, the wheels of government turned much more rapidly and by the spring of 1922 Funakoshi (53 years old) found himself giving a lecture at the Women’s Higher Normal School at the behest of the Monbasho (the Ministry Of Education). His years of school teaching served him well. He was highly prepared and organized and wrote numerous scrolls detailing kata and application. His presentation, which demonstrated this brutal Okinawan martial skill in a refined manner befitting Japanese Budo and capable of being utilized for mass instruction, caught the eye of Jigoro Kano, the influential founder of judo. Immediately following the presentation Funakoshi was approached and asked to demonstrate at Kano’s Kodokan Dojo.

This demonstration, organized by Gichen Funakoshi, included such famous martial artists as Chojun Miyagi (founder of Goju karate) and Shinko Matayoshi (the Okinawan weapons expert who had earlier demonstrated his art with Funakoshi in Kyoto). After they impressed the prince, the wheels of government turned much more rapidly and by the spring of 1922 Funakoshi (53 years old) found himself giving a lecture at the Women’s Higher Normal School at the behest of the Monbasho (the Ministry Of Education). His years of school teaching served him well. He was highly prepared and organized and wrote numerous scrolls detailing kata and application. His presentation, which demonstrated this brutal Okinawan martial skill in a refined manner befitting Japanese Budo and capable of being utilized for mass instruction, caught the eye of Jigoro Kano, the influential founder of judo. Immediately following the presentation Funakoshi was approached and asked to demonstrate at Kano’s Kodokan Dojo.

Five years later Kano also visited Chokki Motobu (another early pioneer of karate) in Okinawa during his visit to the island in 1927 (7). Judging from Motobu’s account, one gets the impression that Kano considered Motobu’s Karate-jutsu perhaps a bit too brutal for his purposes. Kano, we must remember, had been well versed in the brutal techniques of several classical Jujutsu systems and saw the decline of these systems as a result. It was, after all, his synthesis and modification of the techniques found in several of these systems that he used to create his new form “Judo,” which he regarded as a more humane, yet effective, martial way that could be beneficial to all.

Five years later Kano also visited Chokki Motobu (another early pioneer of karate) in Okinawa during his visit to the island in 1927 (7). Judging from Motobu’s account, one gets the impression that Kano considered Motobu’s Karate-jutsu perhaps a bit too brutal for his purposes. Kano, we must remember, had been well versed in the brutal techniques of several classical Jujutsu systems and saw the decline of these systems as a result. It was, after all, his synthesis and modification of the techniques found in several of these systems that he used to create his new form “Judo,” which he regarded as a more humane, yet effective, martial way that could be beneficial to all.

Before one hundred spectators at the Kodokan, Gichen Funakoshi performed his favorite Kata Kusanku Dai (later renamed Kanku in Japan) while his assistant Makoto “Shinken” Gima performed Naihanchi (8). Gima had trained in Okinawa with Kentsu Yabu (a student of Itosu and teacher of the famous karate expert Shigeru Nakamura who later founded Okinawan Kempo) prior to coming to Tokyo and served as a perfect assistant.

Kano soon asked Funakoshi to set up a karate branch of the Kodokan, but to his credit Funakoshi politely declined the offer, perhaps fearing a loss of creative control over the future development of the art. (It is interesting to note that Karate was first recognized by the Butokukai as being a branch of the Judo Division).

Funakoshi remained in Japan, determined to succeed in the popularization of Karate-do on mainland Japan, a dream his dear teacher Itosu had never lived to see. Securing lodging in a dormitory for Okinawan students (the Mesei Juku), he earned his lodging by gardening and performing odd jobs and handy work.

Slowly but surely word spread and Funakoshi began to find students. Realizing that changes were needed if Karate was to be accepted in this very nationalistic period in Japan’s history he began promoting on the mainland (Japan proper) the characters for Empty Hand (meaning Karate) which had been previously referred to by Chomo Hanashiro in order to distance the art from its Chinese influences. He then set about to change the names of the Kata to names which he felt would be more pleasing to the Japanese (9). Times change, he reasoned, and the Karate now taught was vastly different than that which he learned as a child (10). Funakoshi also sought to refine the art even further for the benefit of “young and old, boys and girls, men and woman” (11).

Slowly but surely word spread and Funakoshi began to find students. Realizing that changes were needed if Karate was to be accepted in this very nationalistic period in Japan’s history he began promoting on the mainland (Japan proper) the characters for Empty Hand (meaning Karate) which had been previously referred to by Chomo Hanashiro in order to distance the art from its Chinese influences. He then set about to change the names of the Kata to names which he felt would be more pleasing to the Japanese (9). Times change, he reasoned, and the Karate now taught was vastly different than that which he learned as a child (10). Funakoshi also sought to refine the art even further for the benefit of “young and old, boys and girls, men and woman” (11).

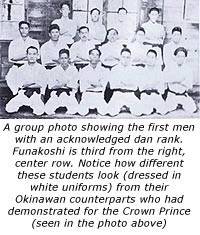

These changes soon paid off, and his classes steadily grew. Calling upon such talented Okinawan Karate-ka as Tsuyoshi Chitose (who had been studying at medical school in Tokyo), Funakoshi had someone to teach for him when he was otherwise unavailable. He soon developed a base of talented Japanese Karate-ka, and on April 12, 1924, Gichen Funakoshi awarded the first Dan rank in the martial art of Karate-do to his assistant Gima. This move is important and can be seen as acquiescence to Dai Nippon Butokukai standards which promoted the adoption of common ranks, belts and uniforms for martial arts in Japan, elements lacking in karate as previously practiced in Okinawa.

Gima’s cousin Tokuda Anbun, already a highly talented Karate-ka in Okinawa, was awarded Nidan with five other first Dan diploma’s being awarded to Otsuka, Kasuya, Akiba, Shimizu and Hirose. These fine instructors proved to be instrumental in spreading Funakoshi’s Karate.

Although by 1934 the highly talented Otsuka went his own way (forming the Wado ryu style which was officially recognized in 1939), his void was temporarily filled by Takeshi Shimoda. Shimoda was Funakoshi’s most talented student (12) (a fact referred to by Shigeru Egami, a senior student of Funakoshi), but during the course of traveling and demonstrating, he became ill and died rather abruptly ending what would have been a most promising future.

Enter Waka Sensei

The master’s third son, Gigo, had been working as an x-ray technician at Tokyo Imperial University and the Ministry of Education, and he himself had been training in Karate since childhood. (13)Affectionately called Waka Sensei (young teacher) he was the perfect replacement for Shimoda. A powerful Karate-ka and a talented technician, he was an innovator in his own right. Combining his youthful vigor with a love of sparring, he became the role model of many young students of the Shoto Kan (House of Shoto, as it was then called), and this undoubtedly played a significant part in the changes that came about in technique as many sought to emulate him.

The master’s third son, Gigo, had been working as an x-ray technician at Tokyo Imperial University and the Ministry of Education, and he himself had been training in Karate since childhood. (13)Affectionately called Waka Sensei (young teacher) he was the perfect replacement for Shimoda. A powerful Karate-ka and a talented technician, he was an innovator in his own right. Combining his youthful vigor with a love of sparring, he became the role model of many young students of the Shoto Kan (House of Shoto, as it was then called), and this undoubtedly played a significant part in the changes that came about in technique as many sought to emulate him.

According to Egami (14), of the original 19 kata of the Shotokan designated for study, the three Taikyoku Kata as well as the Ten no Kata (Omote and Ura) were all created by Gigo. Tragically Gigo’s role was cut short when in November of 1945 he succumbed to tuberculosis. This was truly a heartbreaking blow to Funakoshi, who in March of that very year had seen the Dojo of his dreams utterly destroyed by allied bombing.

The War Ends

Upon the conclusion of the war, devastation prevailed, and Funakoshi’s Okinawan home land paid a heavy price in the fighting. The practice of the martial arts was banned by the army of occupation (though some groups practiced in private). Funakoshi, who had not seen his wife in twenty three years, went to be with her in southern Japan (Kyushu) where she had fled during the fighting in Okinawa. She passed away in 1947.

The year 1948 saw the lifting of the ban on practicing the martial ways, and two former students of Funakoshi, Masatoshi Nakayama and Isao Obata, formed a new organization calling it the Japan Karate Association. Karate again was promoted and popularized and soon instruction was sought out by members of the very army of occupation who had previously banned its practice. To the master’s joy, Karate was now an international art as service members began to open schools and request instructors upon returning home. Even this was not without its disappointment, however, for in the growth of Karate, Funakoshi also saw his students at odds with one another as rival factions formed. It is perhaps the tone of this change that we pick up in the Preface To The Second Edition (dated October 13, 1956) in the1973 reprint of Funakoshi’s book, “Karate do Kyohan,” in which he said:

“As a result of the social disorder that followed the end of World War II, the karate world was dispersed, as were many other things. Quite apart from a decline in the level of technique during these times, I cannot deny that there were moments at which I came to be painfully aware of the almost unrecognizable spiritual state to which the karate world had come from that had prevailed at the time I had first introduced and begun teaching of karate. Although one might claim that such changes are only the natural result of expansion of Karate-do, it is not evident that one should view such a result with rejoicing rather than with some misgiving.”

Gichen Funakoshi passed away on April, 1957 always clutching the torch.

Here you can find rare documentary vintage movie of sensei Funakoshi.

Footnotes:

(1) As noted on page one of “Karatedo My Way Of Life,” Funakoshi notes that he falsified the official record date of 1870 and that his actual birth date was two years earlier. The reason he did this was to meet the age requirements to sit for the entrance exams to medical school.

(2) A choice also made by such Notables as Gusakuma Shinpan and Kyoda Juhatsu.

3) As recounted by Funakoshi on pages 19 and 20 of “Karatedo My Way Of Life”: “I frequently took my children to their homes where on these occasions they would demonstrate certain kata for the children, then bid the children to do the same.”

(4) Page 21 of “Karatedo My Way Of Life,” by Gichin Funakoshi.

(5) Nagamine recounts on page 71 of his book, “Tales Of Okinawa’s Great Masters,” translated by Patrick McCarthy.

(6) On page 65 of “Unante – The Secrets Of Karate,” John Sells (the author) notes the exact date of the visit as March 6, 1921.

(7) Choki Motobu is quoted as recounting his meeting with Kano (which was witnessed by Marukawa Kenji, a direct student of Motobu), in the essay “Motobu Choki Sensei: Goroku,” by Nakata Hashihiko which was published 1978, here translated by Joe Swift: “When I was still in Okinawa, Jigoro Kano of the Kodokan came to visit and asked to talk to me. Through a friend we went to a certain restaurant. Mr. Kano talked about a lot of things, but about karate, he asked me what would I do if my punch missed. I answered I would immediately follow up with an elbow from that motion. After that he became quiet and asked nothing about karate.”

(8) As stated by John Sells on page 67 of “Unante – The Secrets Of Karate.”

(9) As found on page 36 of “Karatedo My Way Of Life” by Funakoshi.

(10) As found on page 36 of “Karatedo My Way Of Life” by Funakoshi.

(11) As found on page 36 of “Karatedo My Way Of Life” by Funakoshi.

(12) As found on Page 11 of “The Heart Of Karatedo” by Shigeru Egami. Although Egami developed his own following he remained close to Funakoshi and was devoted to preserving his original teachings.

(13) On page 20 of “Karatedo My Way Of Life,” Funakoshi recounts how his children came to love Karate and began to visit the two masters by themselves just as he had done.

(14) According to Egami on Page 103 of “The Heart of Karatedo”

References:

“Karatedo My Way Of Life” by Gichin Funakoshi, Kodansha 1981.

“The Heart of Karatedo” by Shigeru Egami Revised edition, Kodansha 2000.

“Karatedo Nyumon” by Gichin Funakoshi, Kodansha 1994.

“Karatedo Kyohan” by Gichin Funakoshi, Kodansha.

“Tales Of The Great Okinawan Masters” by Shoshin Nagamine, translated by Patrick McCarthy, Tuttle 1999.

“Unante – The Secrets Of Karate” by John Sells, Hawley 1996.

Photos:

Funakoshi photos were reproduced from his 1935 book, Karatedo Kyohan. The group portrait of Funakoshi dan ranking students was provided courtesy of Masters Publications.

The Itosu drawing was contributed by Kyoshi Frank Hargrove from his book, The 100 Year History of Shorin-Ryu Karate. Since there are no known photos of Itosu, the drawing was a composite done in Okinawa based on available descriptions.

Written by Tom Ross