Sai is a weapon that belongs to the arsenal of the okinawan kobudo. The exact date of its arrival to Okinawa is unknown

, but the similar tools can be found throughout the coast of South Asia. There is an assumption that sai has been brought from China, where similar kinds of weapon can be found in the arsenals of the different kinds of chua –fa traditions. One theory says that this weapon was based on a similar tool that was used for making holes in the ground for planting rice. Nevertheless, since there is no solid proof, the origin of the sai has remained unknown.

Before 1900, sai was used by the members of the local police “chikusaji” for doing their duty and for self-protection. They were in charge for guarding the palace, collecting tax, maintaining the order and catching outlaws. Before the appearance of the fire weapon, staff was most common weapon used in physical confrontation. General population used different kinds of sticks, wands, clubs and hoes in daily work and in self-defense. Sai was the ideal weapon for defending oneself against attacker with a stick or a club, because it enables catching the opponent’s weapon and disarming.

Before 1900, sai was used by the members of the local police “chikusaji” for doing their duty and for self-protection. They were in charge for guarding the palace, collecting tax, maintaining the order and catching outlaws. Before the appearance of the fire weapon, staff was most common weapon used in physical confrontation. General population used different kinds of sticks, wands, clubs and hoes in daily work and in self-defense. Sai was the ideal weapon for defending oneself against attacker with a stick or a club, because it enables catching the opponent’s weapon and disarming.

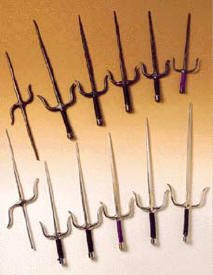

In the early days, there used to be many different types of this weapon, but nowadays its form is standardized. Sai is used as a couple, but there has been a custom to carry the third sai by the belt. This third sai could be used in case one sai was being thrown at the opponent, sort of like a reserve one. There is a characteristic sai called “manji sai”, which arm guard has a shape of the letter “S”. The kobudo expert Shinko Matayoshi, saw this weapon in Shanghai (China) and brought it later to Okinawa.

In the early days, there used to be many different types of this weapon, but nowadays its form is standardized. Sai is used as a couple, but there has been a custom to carry the third sai by the belt. This third sai could be used in case one sai was being thrown at the opponent, sort of like a reserve one. There is a characteristic sai called “manji sai”, which arm guard has a shape of the letter “S”. The kobudo expert Shinko Matayoshi, saw this weapon in Shanghai (China) and brought it later to Okinawa.

Matayoshi tradition

Matayoshi Shinko, sensei, also known as “Kama Matayoshi” was born in Naha (Okinawa) in 1888. In his youth, the master Agena Chukubo, from the Gushikawa village, taught him bo-jitsu (the stick), eku-jitsu (oar) and kama-jitsu (sickles).

Matayoshi Shinko, sensei, also known as “Kama Matayoshi” was born in Naha (Okinawa) in 1888. In his youth, the master Agena Chukubo, from the Gushikawa village, taught him bo-jitsu (the stick), eku-jitsu (oar) and kama-jitsu (sickles).

He also learned tonfa-jitsu (wand) and nunchaku-jitsu (mallet) from the master Irei of Nozatoa (Chatan village). After that, he was traveling with the purpose of expanding his knowledge. In Japan, he learned samurai horse riding. In Manchuria, he had spent much time with nomad tribes, where he practiced ba-jitsu (horse riding), shuriken-jitsu and nagenawa-jitsu (lasso throwing). In Shanghai, the master Kingai taught him tinbei-jitsu (a sword and a shield), suruchin-jitsu (lasso), nunti-jitsu (javelin) and use of the medicinal herbs and acupuncture as well. In the province of Fukien (China), he practiced Shorin chuan fa and finally, he returned to Okinawa in 1935.

When the Japanese emperor visited Okinawa in 1915, a demonstration of all traditional okinawan martial arts was organized in his honor. Shinko sensei had the honor of demonstrating kobudo showing the use of tonfa and kama, whereas Funakoshi sensei (founder of Shotokan) demonstrated karate. These facts confirm that master Shinko was one of the greatest kobudo experts on Okinawa at that time.

Matayoshi Shinko died in 1947, in the 59th age of his life. His son Shinpo (1921-1997) continued family tradition. Thanks to him, there are Matayoshi kobudo schools all over the world today. It should be emphasized that Matayoshi tradition cherishes tradition of many weapons and it is not like: “one should learn a little bit of everything…”, on contrary it is completely preserved traditional weapon system based on the knowledge of origin and characteristics of each weapon. It takes many years of practice for someone to master only one weapon.

Basics (kihon)

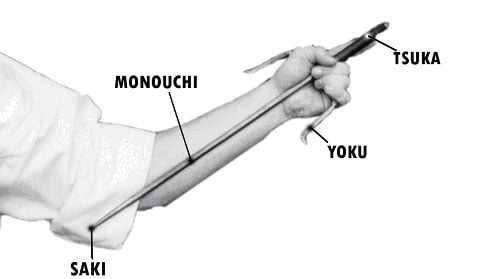

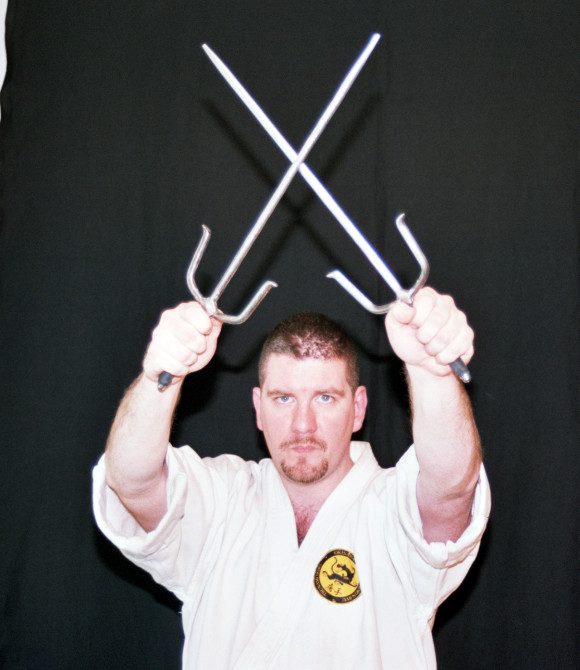

At first look, sai looks like kind of a dagger, but actually, its practical application is similar to club use. This weapon has no blade or cutting edge, so it is not intended for slashing but rather for striking. The top (saki) is dull, which implies that it was not designed for causing mortal wounds. The main purpose of this weapon is to hurt and repulse an attacker. Above the handle (tsuka), there is a hand guard (yoku) especially shaped for not only protecting the hand, but also for catching the opponent’s weapon and disarming as well.

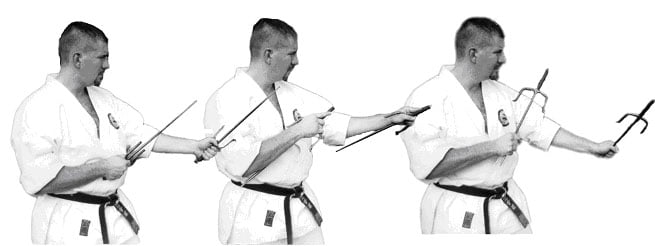

There are three basic ways of holding this arm. “The offensive hold” is used for striking (uchi), catching (kake uke), and stabbing (saki tsuki). “The defensive hold” enables blocking with forearm because “the blade” is leaned on the forearm and thrusting with the handle (tsuka). The third way of holding is rare, but there are a few traditions on Okinawa using this type of hold. Sai is held by “the blade” (monouchi) and the use is similar to the use of kama (sickles); in different words, it’s used for striking as in striking with “a hammer”, and hooking with the yoku.

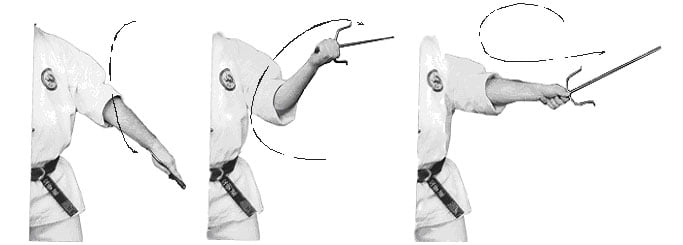

Beginners start with basic manipulating exercise. They practice swift grip changing, through three basic positions (tsoken, haku & shitu). Sai needs to be held in a relaxed manner because it enables fast manipulation. Grip should be tight in last moment, when contact with opponent is made. Fluid sai manipulation reveals if the person is a beginner or a master.

The thrusts (tsuki)

There are two basic ways of direct thrust (tsuki) and they are performed the same way all the punches in karate are done. The first one is the stab with the sai top (saki tsuki) which is directed towards neck, chest and stomach of the attacker. The second way includes the handle (tsuka) for thrusts in the face, neck or the attacker’s chest.

The strikes (uchi)

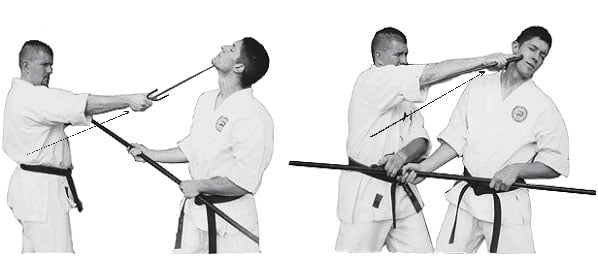

A strike with “the blade” (monouchi) is performed from the outer side (soto) or the inner side (uchi), with the arm swing and wrist contraction. The secret key is to utilize the weight of the weapon, for power generation. Uchi techniques are equally effective in offense and in defense. Offensive strikes (uchi) are generally directed towards face, but sometimes at the attacker’s hands as well, which provides disarming. Defensively, uchi techniques are used for blocking by striking the opponent’s attacks in the same manner as in karate. When one watches, the performing of the kata with sai, at first it is difficult to tell where each of the strike is directed. That is because traditionally, strokes do not stop in place like in karate, they go further down, up to one’s knee. It is done like that, because this way one gets better sense on how to generate powerful strikes. In addition, when technique is executed like this it covers larger area, meaning not only strikes could be aimed at head, but torso, arms and legs as well.

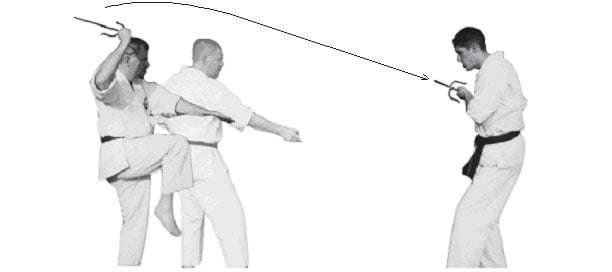

The first picture shows uchi as blocking technique;

the second picture shows uchi as striking technique.

Blocks (uke)

By fast manipulation, sai is easily set in “defensive hold” when “the blade” is leaned on the forearm. This holding position, enables one to block the opponent’s attacks with forearm the same way as in karate – using the upper block (age uke), middle block (soto uke) and lower block (gedan uke).

During blocking, great deal plays the hand-guard (yoku), because it provides catching attacker’s weapon or hand (kake uke).

Throwing

Sai is a pretty heavy and good balanced weapon that can be thrown. In Shinbaru form, this technique appears twice, when sai is being shoved into the ground, sand or a especially made target. In reality, it is possible to throw sai precisely at the distance of 3 meters, when goal is to penetrate into the attacker’s body. This technique is very effective thanks to sai’s weight. It is also useful when technique is executed from the long distance, because if sai bang into opponents face it can literally knock down the attacker and hurt him very badly.

Advanced application (shinbaru kata bunkai)

I will not spend unnecessary words on theory, because I think the use of sai can be best understood through its actual application. Our school preserves the kobudo tradition of Matayoshi family, and therefore, I will explain the use of the form Shinbaru no sai. First, I will explain what is the attacker doing (tori), and after that, I will explain what defender (uke) should do.

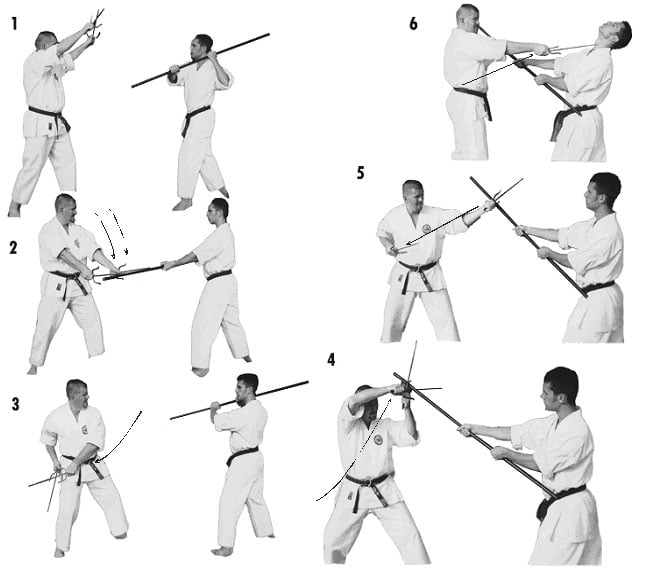

Sequence 1. (age uke-tsuki)

The attacker performs a swing with the staff aiming at the head. Uke performs upper block (age uke) by holding sai in defensive kamae and thrusts back with the handle of the dagger (tsuki) into opponents face.

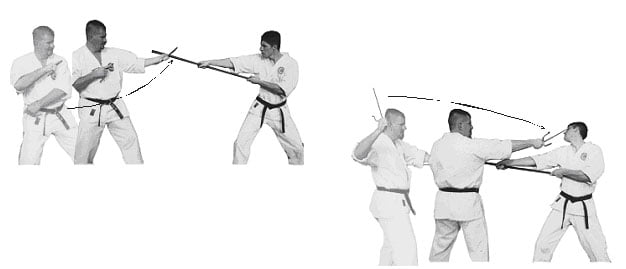

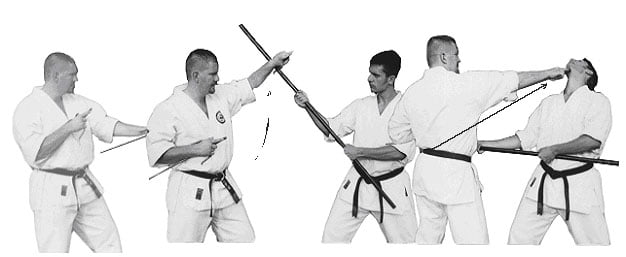

Sequence 2. (soto uke –ura uchi-soto uchi-tsuki)

The attacker performs a thrust trying to poke the neck or face. Uke is blocking with the forearm (soto uke) and momentarily changes the grip and gives counterstrike to attacker’s face (picture 2), then smashing attacker’s hand (picture 3) and finishes with the thrust in the neck (picture 4).

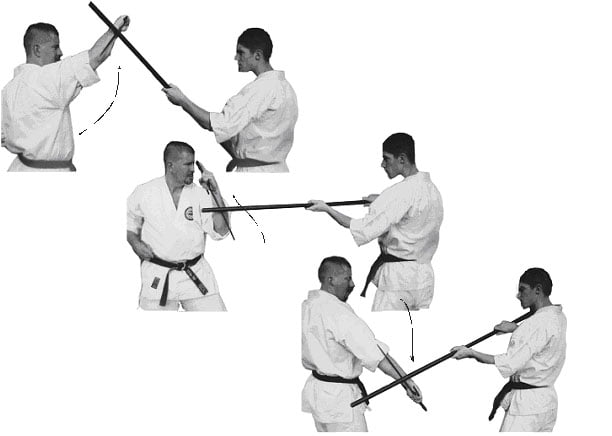

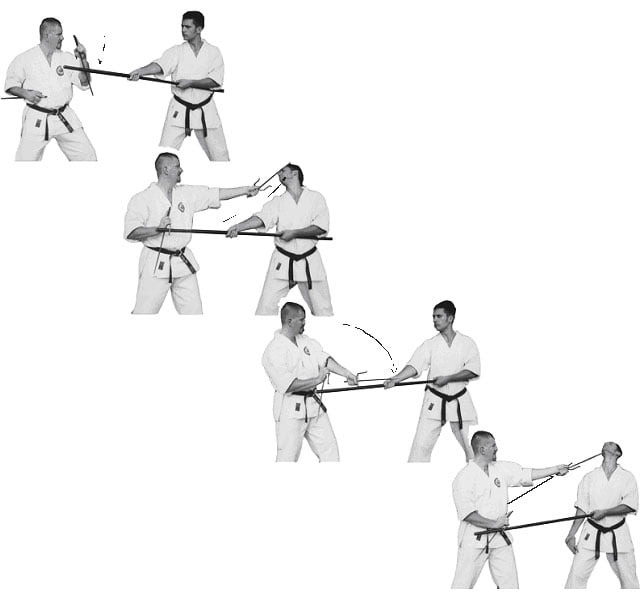

Sequence 3. (age uke-gyaku age uke-tsuki)

The attacker performs two swings, one following another, with the staff aiming to the head. Uke blocks the first swing with his front arm (1), while rear sai is in offensive position ready to stab. Then he performs the quick grip change (both weapons), blocks with the rear hand (2) and performs a thrust with the front hand (3).

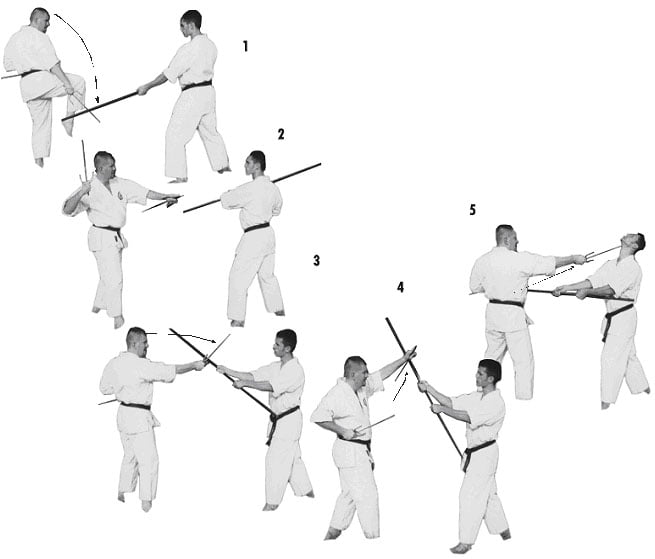

Sequence 4. (gedan uchi-jodan uchi-tsuki)

The attacker performs two swinging strikes; one following another, with the staff, the first one is aiming the legs, and the second one attacking the head. Blocking is done with the strikes (uchi wasa) in the attacker’s weapon, sai is in the offensive position and all techniques are done with one hand. Uke lifts himself in “crane position” (standing on one leg) and blocks by striking the staff (1 – gedan uchi), then protects head with upper strike (3 – jodan uchi), swiftly catches attacker’s staff (4), and finishes with a thrust (saki tsuki) (5).

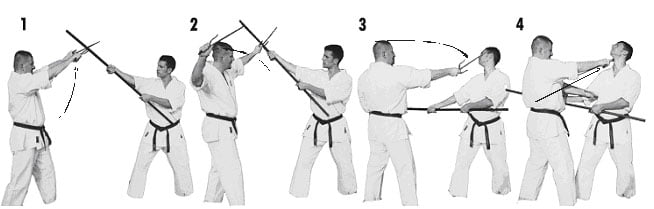

Sequence 5. (moroto uchi-jodan juji uke-tsuki)

What is specific about this sequence is that the attacker’s blows blocked with both weapons at the same time. These “double” blocks are efficient when it comes to the uncontrolled strikes with a staff that performed using big swinging motions. The attacker performs two attacks, one following another, aiming at the head. Uke blocks the first strike, using both weapons (1 – moroto uchi), then he receive second attack using specific “crossed block” (4 – juji uke) which allows him to captivate the attacker’s staff (5) and the thrusts to neck (6 – saki tsuki).

Sequence 6. (moroto age uchi-soto uchi)

This sequence is executed “in passing by”. The attacker performs a staff thrust in the face. Uke blocks with both weapons (1), with the idea of moving away the attacker’s staff and by continuing that move he strikes back in the attacker’s face (3). At the end, defender changes a grip to defensive kamae and finishes with double thrust into opponent’s neck and body (4).

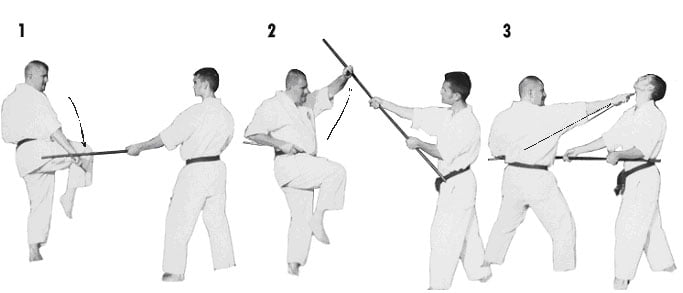

Sequence 7. (gedan uke-jodan uke-tsuki /tsuru ashi dachi/)

The attacker performs two strikes, one following another – first to the body and then aiming the head. Uke blocks first strike (1 – gedan uke), then with the other arm blocks away the blow directed to head (2 – age uke), catches opponent weapon and finishes with thrust.

Author

Author

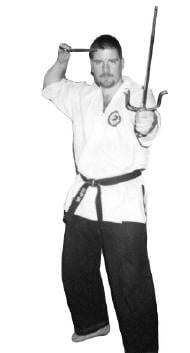

The Author Milos Stanic (4.dan) promotes old okinawan empty hand and weapon traditions (shorin ryu karate & matayoshi kobudo) in Belgrade (Yugoslavia), teaching as professional instructor in Tsunami dojo. He is helping prospering popularity of traditional karate in southeast Europe by organizing karate demonstrations on all important martial art events. In addition, he is also trying to get global attention through website Tsunami dojo (www.karate.org.yu) where he publishes articles and produces educational video material.

Assistants Milutinovic Mirko (1.dan) and Ivanovic Predrag (1. Dan) provided great support while making this article.

All copyrights reserved 2002. (The Author’s right are reserved, this article cannot be copied, published and cannot be used without the written permission of the author.)

Sources

- Bishop, M. (1999) Okinawan Karate: Teachers, Styles and Secret Techniques, 2nd Edition. Boston: Charles E. Tuttle, Co.

- Funakoshi G. (1976) Karatedo: My Way of Life. Tokyo: Kodansha International.

- Funakoshi G. (1988) Karatedo Nyumon. Tokyo: Kodansha International. Tr. by John Teramoto.

- McCarthy, P. (1999) Ancient Okinawan Martial Arts: Koryu Uchinadi, Vol. 2. Boston: Charles E. Tuttle,

- McCarthy, P. (1995) The Bible of Karate – Bubishi. Boston: Charles E. Tuttle, Co.

- Motobu C. (1932) Watashi no Toudijutsu (My Karate). Tokyo: Toudi Fukyukai.

- Nagamine S. (1986) Tales of Okinawa’s Great Karate and Sumo Masters

- Nagamine S. (1978) The Essence of Okinawan Karate-do, Charles E. Tuttle

Author

Author