I am sharing an article by leading Israeli archaeologist Professor Zeev Herzog because it is important for understanding the history of Christianity, and especially crucial for debunking the false “Judeo-Christian” narrative.

Republished in the Biblical Archaeology magazine from Ha’aretz |

Original date: October 1999 | Zeev Herzog

After 70 years of intense excavation in the land of Israel, archaeologists have learned: The patriarchal stories are legendary, we did not reside in Egypt nor did we make an exodus, and we did not conquer the land. Also, there is no mention of the empire of David and Solomon. Those interested in this topic have known these facts for years, but Israel is a stubborn nation that does not want to hear about it.

Here is what archaeologists have learned from their excavations in the land of Israel: The Israelites were never in Egypt, they did not wander in the desert, they did not conquer the land in a military campaign, and they did not pass it on to the 12 tribes of Israel. Perhaps even harder to accept is that the united monarchy of David and Solomon, described in the Bible as a regional power, was at best a small tribal kingdom. Many will also be unpleasantly surprised to learn that the God of Israel, YHWH, had a female consort, and that early Israelite religion adopted monotheism only in the final phase of the monarchy, not at Mount Sinai.

Most of those who work in the interconnected fields of the Bible, archaeology, and Jewish history – and who once entered the field searching for evidence to confirm the biblical story – now agree that the historical events related to the emergence of the Jewish people are radically different from what that story says.

Below is a brief overview of the short history of archaeology, with emphasis on crises and the big bang, so to speak, of the last decade. The key question of this archaeological revolution has yet to penetrate public consciousness but cannot be ignored.

Inventing the Biblical Stories

The archaeology of Palestine developed as a science relatively late, at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century, in tandem with the archaeology of imperial cultures such as Egypt, Mesopotamia, Greece, and Rome. These resource-intensive regions were the primary target for researchers seeking impressive evidence from the past, usually in the service of major museums in London, Paris, and Berlin. This phase effectively bypassed Palestine, with its fragmented geographic diversity. The conditions in ancient Palestine were not conducive to the development of a vast kingdom, and certainly no major projects such as Egyptian temples or Mesopotamian palaces could have been founded there. In fact, Palestinian archaeology did not arise from museum initiatives but from religious motives.

The main incentive for archaeological research in Palestine was the land’s connection to the Holy Scripture. The first excavators in Jericho and Shechem (Nablus) were biblical researchers looking for remnants of cities mentioned in the Bible. Archaeology gained momentum through the activities of William Foxwell Albright, who mastered the archaeology, history, and languages of the land of Israel and the ancient Near East. Albright, an American whose father was a Chilean-born priest, began excavating in Palestine in the 1920s. His declared research approach was that archaeology was the primary scientific tool for refuting critical claims against the historical veracity of biblical stories, particularly those of the Wellhausen school in Germany.

The school of biblical criticism, which developed in Germany in the second half of the 19th century, led by Julius Wellhausen, questioned the historical reliability of biblical stories and claimed that biblical historiography was formulated and largely ‘invented’ during the Babylonian exile. Biblical scholars, especially Germans, argued that the history of the Hebrews, as a continuous series of events beginning with Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, and continuing through the journey to Egypt, slavery, and the exodus, culminating in the conquest of the land and the settlement of the tribes of Israel, was in fact simply a later reconstruction of events for theological purposes.

Albright believed that the Bible was a historical document that, although having undergone several stages of editing, still fundamentally reflected ancient reality. He was convinced that if the ancient remains of Palestine were uncovered, they would provide unequivocal evidence of the historical truth of the events relating to the Jewish people in their land.

The biblical archaeology that developed after Albright and his disciples led to a series of extensive excavations at important biblical sites: Megiddo, Lachish, Gezer, Shechem (Nablus), Jericho, Jerusalem, Ai, Gibeon, Beth Shean, Beth Shemesh, Hazor, Ta’anach, and others. The path was straight and clear: every new find contributed to building a harmonious picture of the past. Enthusiastic archaeologists who adopted the biblical approach set out to search for the ‘biblical period’: the period of the patriarchs, the Canaanite cities destroyed by the Israelites during the conquest of the land, the borders of the 12 tribes, the settlement period sites, characterized by ‘settler pottery’, ‘Solomon’s gates’ at Hazor, Megiddo, and Gezer, ‘Solomon’s stables’ (or Ahab’s), ‘King Solomon’s mines’ in Timna — and some are still diligently searching, having found Mount Sinai (on Mount Karkum in the Negev) or Joshua’s altar on Mount Ebal.

The Crisis

Gradually, cracks began to appear in the picture. Paradoxically, a situation arose in which a mass of findings began to undermine the historical credibility of the biblical accounts instead of strengthening them. A crisis phase occurs when theories within the overall thesis cannot address an increasing number of anomalies.

Explanations become difficult and inelegant, and the pieces do not fit together smoothly. Here are a few examples of how the harmonious picture collapsed.

The Patriarchal Period:

Researchers had difficulty agreeing on which archaeological period corresponds to the Patriarchal Period. When did Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob live? When was the Cave of Machpelah (Tomb of the Patriarchs in Hebron) purchased to serve as a burial place for the patriarchs and matriarchs? According to biblical chronology, Solomon built the Temple 480 years after the exodus from Egypt (1 Kings 6:1). To this period, we must add 430 years of residence in Egypt (Exodus 12:40) and the long lifespans of the patriarchs, giving a date in the 21st century BCE for Abraham’s migration to Canaan. However, no evidence has been found to support this chronology. In the early 1960s, Albright advocated placing Abraham’s wandering in the Middle Bronze Age (22nd–20th century BCE). However, Benjamin Mazar, the father of Israel’s branch of biblical archaeology, proposed identifying the historical background of the Patriarchal Period a thousand years later, in the 11th century BCE — placing it in the ‘settlement period’. Others rejected the historicity of the stories, considering them ancestral legends recounted during the Judean Kingdom period. In any case, consensus began to crumble.

Researchers had difficulty agreeing on which archaeological period corresponds to the Patriarchal Period. When did Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob live? When was the Cave of Machpelah (Tomb of the Patriarchs in Hebron) purchased to serve as a burial place for the patriarchs and matriarchs? According to biblical chronology, Solomon built the Temple 480 years after the exodus from Egypt (1 Kings 6:1). To this period, we must add 430 years of residence in Egypt (Exodus 12:40) and the long lifespans of the patriarchs, giving a date in the 21st century BCE for Abraham’s migration to Canaan. However, no evidence has been found to support this chronology. In the early 1960s, Albright advocated placing Abraham’s wandering in the Middle Bronze Age (22nd–20th century BCE). However, Benjamin Mazar, the father of Israel’s branch of biblical archaeology, proposed identifying the historical background of the Patriarchal Period a thousand years later, in the 11th century BCE — placing it in the ‘settlement period’. Others rejected the historicity of the stories, considering them ancestral legends recounted during the Judean Kingdom period. In any case, consensus began to crumble.

Exodus from Egypt, Wandering in the Desert, and Mount Sinai:

Many Egyptian documents in our possession do not mention the presence of Israelites in Egypt, nor do they speak of the events of the Exodus. Many documents mention the practice of nomadic shepherds entering Egypt during periods of drought and famine and camping on the outskirts of the Nile Delta. However, this was not an isolated phenomenon: such events occurred frequently over thousands of years and were not particularly exceptional. Generations of researchers have attempted to locate Mount Sinai and the camps of the tribes in the desert. Despite these intense efforts, no location has been found that matches the biblical account.

Many Egyptian documents in our possession do not mention the presence of Israelites in Egypt, nor do they speak of the events of the Exodus. Many documents mention the practice of nomadic shepherds entering Egypt during periods of drought and famine and camping on the outskirts of the Nile Delta. However, this was not an isolated phenomenon: such events occurred frequently over thousands of years and were not particularly exceptional. Generations of researchers have attempted to locate Mount Sinai and the camps of the tribes in the desert. Despite these intense efforts, no location has been found that matches the biblical account.

The strength of tradition has now led some researchers to “discover” Mount Sinai in northern Hijaz or, as already mentioned, on Mount Karkum in the Negev. The central events in the history of the Israelites are not confirmed in documents outside of the Bible nor in archaeological findings. Most historians today agree that the stay in Egypt and the events of the Exodus, at best, involved a few families and that their private story was expanded and “nationalized” to suit the needs of theological ideology.

The Conquest:

One of the formative events of the people of Israel in biblical historiography is the story of how the land was conquered from the Canaanites. However, very serious difficulties have arisen precisely in attempts to locate archaeological evidence for this story. Repeated excavations by various expeditions in Jericho and Ai, two cities whose conquests are most detailed in the Book of Joshua, have been very disappointing. Despite the efforts of the excavators, it turned out that in the late 13th century BCE, at the end of the Late Bronze Age, which is the agreed-upon period for the conquest, there were no cities in any part, and, of course, there were no walls that could have been brought down. Naturally, explanations were offered for these anomalies. Some claimed that the walls around Jericho were washed away by rain, while others suggested that earlier walls were used; and, as for Ai, it was argued that the original story actually referred to the conquest of nearby Bethel and was later transferred to Ai by later editors.

Biblical scholars proposed a quarter of a century ago that the conquest stories be viewed as etiological legends and nothing more. But as more and more locations were discovered and it turned out that the places in question were extinct or simply abandoned at different times, the conclusion that there is no factual basis for the biblical story of the conquest by the Israelite tribes in a military campaign led by Joshua was strengthened.

Canaanite Cities:

The Bible exaggerates the strength and fortifications of the Canaanite cities that the Israelites allegedly conquered: “great cities with walls up to the sky” (Deuteronomy 9:1). In practice, all the sites that have been discovered show remains of unfortified settlements, which in most cases consisted of a few structures or a ruler’s palace, rather than a true city. The urban culture of Palestine in the Late Bronze Age disintegrated in a process that lasted hundreds of years and did not result from military conquest.

The Bible exaggerates the strength and fortifications of the Canaanite cities that the Israelites allegedly conquered: “great cities with walls up to the sky” (Deuteronomy 9:1). In practice, all the sites that have been discovered show remains of unfortified settlements, which in most cases consisted of a few structures or a ruler’s palace, rather than a true city. The urban culture of Palestine in the Late Bronze Age disintegrated in a process that lasted hundreds of years and did not result from military conquest.

Moreover, the biblical description is not familiar with the geopolitical reality in Palestine. Palestine was under Egyptian rule until the middle of the 12th century BCE. Egyptian administrative centers were located in Gaza, Jaffa, and Beth Shean. Egyptian presence has been discovered at many sites on both sides of the Jordan River. This conspicuous presence is not mentioned in the biblical account, and it is clear that it was unknown to the author and his editors. Archaeological findings clearly contradict the biblical picture: the Canaanite cities were not “great”, they were not fortified, and they did not have “walls up to the sky.” The heroism of the conquerors, the few against the many, and the help of God fighting for His people is a theological reconstruction without any factual basis.

The Origin of the Israelites:

The conclusions drawn from the episodes of the formation of the people of Israel together have led to a debate over the fundamental question: the identity of the Israelites. If there is no evidence for the exodus from Egypt and the journey through the desert, and if the story of the military conquest of fortified cities has been rejected by archaeology, who were the Israelites? Archaeological findings have confirmed one important fact: in the early Iron Age (beginning sometime after 1200 BCE), the phase identified with the “settlement period,” hundreds of small settlements were established in the central hill country of the land of Israel, inhabited by farmers who cultivated the land or raised sheep. If they did not come from Egypt, what was the origin of these settlers?

Israel Finkelstein, a professor of archaeology at Tel Aviv University, proposed that these settlers were simple shepherds who roamed this hilly region during the Late Bronze Age (the graves of these people have been found, but without settlements). According to his reconstruction, in the Late Bronze Age (which preceded the Iron Age), the shepherds maintained a trade economy of meat in exchange for grains with the inhabitants of the valleys. With the collapse of the urban and agricultural system in the lowlands, the nomads were forced to produce their own grains, and hence the need for stable settlements arose.

The name “Israel” is mentioned in an Egyptian document from the period of Pharaoh Merneptah, king of Egypt, dating to 1208 BCE: “Canaan is plundered with all evil, Ashkelon is captured, Gezer is seized, Yenoam is as if it never existed, Israel is laid waste, his seed is no more.” Merneptah refers to the land by its Canaanite name and mentions several city-kingdoms along with a non-urban ethnic group. According to this evidence, the term “Israel” was assigned to one of the population groups inhabiting Canaan at the end of the Late Bronze Age, apparently in the central hill country, in the area where the Kingdom of Israel would later be established.

A Kingdom without a Name

The United Monarchy: Archaeology is also a source that has led to shifts in the reconstruction of reality during the period known as the ‘United Monarchy’ of David and Solomon. The Bible describes this period as the zenith of Israel’s political, military, and economic power in ancient times. Due to David’s conquests, the empire of David and Solomon stretched from the Euphrates River to Gaza (“For he ruled over all the region west of the Euphrates, from Tiphsah to Gaza, over all the kings west of the Euphrates”, 1 Kings 5:4). Archaeological findings at many locations show that the construction projects attributed to this period were modest in scope and power.

Three cities, Hazor, Megiddo, and Gezer, which are mentioned among Solomon’s building enterprises, have been thoroughly excavated in the relevant layers. Only about half of Hazor’s upper city was fortified, covering an area of only 30 dunams (7.5 acres), out of a total area of 700 dunams that had been settled in the Bronze Age. In Gezer, there was apparently only a citadel surrounded by a casemate wall, covering a small area, while Megiddo was not fortified with a wall.

The picture becomes even more complex in light of excavations conducted in Jerusalem, the capital of the United Monarchy. Large parts of the city have been excavated over the last 150 years. The excavations have revealed impressive remains of cities from the Middle Bronze Age and from Iron Age II (the period of the Kingdom of Judah). No remains of buildings from the United Monarchy period (even according to the agreed chronology) have been found, except for a few pottery fragments. Given the preservation of remains from earlier and later periods, it is clear that Jerusalem in the time of David and Solomon was a small city, perhaps with a small citadel for the king, but in any case, it was not the capital of an empire as described in the Bible.

This small tribal state is the source of the name ‘House of David’ mentioned in later Aramean and Moabite inscriptions. The authors of the biblical account were familiar with Jerusalem in the 8th century BCE, with its walls and rich culture, the remains of which have been found in various parts of the city, and projected this image back to the time of the United Monarchy. It is assumed that Jerusalem gained its central status after the destruction of Samaria, its northern rival, in 722 BCE.

Archaeological findings fit well with the conclusions of the critical school of biblical scholarship. David and Solomon were rulers of tribal kingdoms that controlled small areas: David in Hebron and Solomon in Jerusalem. At the same time, a separate kingdom began to form in the hills of Samaria, expressed in the stories of Saul’s kingdom. Israel and Judah were from the beginning two separate, independent kingdoms and were sometimes in conflict. Therefore, the grand United Monarchy is an imaginary historiographical creation that arose no earlier than the Kingdom of Judah period. Perhaps the most compelling evidence for this is that we do not know the name of this kingdom.

YHWH and His Consort

How many gods did Israel have? Along with the historical and political aspects, there are also doubts about the accuracy of the information regarding belief and worship. The question of when monotheism was adopted by the kingdoms of Israel and Judah arose with the discovery of inscriptions in ancient Hebrew mentioning a pair of gods: YHWH and His Asherah. In two places, Kuntillet Ajrud in the southwestern Negev highlands, and Khirbet el-Qom at the foot of the Judean hills, Hebrew inscriptions were found mentioning ‘YHWH and His Asherah’, ‘YHWH of Samaria and His Asherah’, and ‘YHWH of Teman and His Asherah’. The authors were familiar with the pair of gods, YHWH and His consort Asherah, and sent blessings in the name of the pair. These inscriptions, from the 8th century BCE, raise the possibility that monotheism, as a state religion, was actually an innovation of the Kingdom of Judah after the destruction of the Kingdom of Israel.

The archaeology of the land of Israel has completed a process that can be considered a scientific revolution in its field. It is ready to confront the findings of biblical scholarship and ancient history as an equal discipline. But at the same time, we are witnessing a fascinating phenomenon where all of this is simply ignored by the Israeli public. Many of these findings have been known for decades. Scholarly literature in the fields of archaeology, the Bible, and the history of the Jewish people has processed them in dozens of books and hundreds of articles. Even if not all scholars accept the individual arguments that inform the examples I’ve mentioned, most have adopted their main points. Yet, these revolutionary views do not penetrate the public consciousness.

About a year ago, my colleague, historian Prof. Nadav Na’aman, published an article in the Ha’aretz Culture and Literature section titled ‘Removing the Bible from the Jewish Bookshelf,’ but there was no public outcry. To any critically-minded person, it will be obvious that removing the people of Israel from these contexts is only the beginning. Israel is a threat to our historical justice.

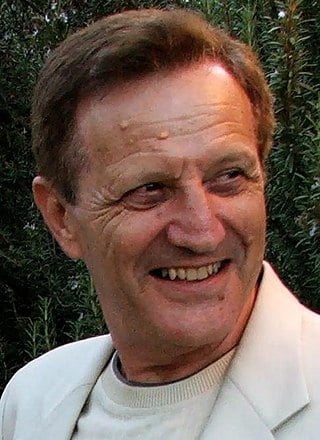

Prof. Zeev Herzog teaches at the Department of Archaeology and Ancient Near Eastern Studies at Tel Aviv University. He participated in excavations at Hazor and Megiddo with Yigael Yadin and in excavations at Tel Arad and Tel Beersheba with Yohanan Aharoni. He has led excavations at Tel Michal and Tel Gerisa and recently began excavations at Tel Jaffa. He is the author of books on the city gate in Palestine and its neighbors, as well as two excavation reports, and has written a book summarizing the archaeology of the ancient city.

Prof. Zeev Herzog teaches at the Department of Archaeology and Ancient Near Eastern Studies at Tel Aviv University. He participated in excavations at Hazor and Megiddo with Yigael Yadin and in excavations at Tel Arad and Tel Beersheba with Yohanan Aharoni. He has led excavations at Tel Michal and Tel Gerisa and recently began excavations at Tel Jaffa. He is the author of books on the city gate in Palestine and its neighbors, as well as two excavation reports, and has written a book summarizing the archaeology of the ancient city.