Recently, I bought a book – “Bulgarian Antiquities from Macedonia” by Professor Jordan Ivanov, published in 1931 in Sofia by the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences.

The book is very interesting because many things overlap between the history of Serbs and Bulgarians, which, of course, is not surprising since Serbs and Bulgarians were practically one people until the 19th century and spoke the same language.

The book is very interesting because many things overlap between the history of Serbs and Bulgarians, which, of course, is not surprising since Serbs and Bulgarians were practically one people until the 19th century and spoke the same language.

Old Slavic Texts

I started reading a bit in Old Serbian or Old Slavic, whichever term you prefer. Both are correct. It was indeed the Old Serbian language during the Nemanjić era, but it should be noted that Saint Sava, in the “Zakonopravilo,” says, “I brought these books to light in the Slavic language.” From Saint Sava’s writings, it is evident that under the term “Slavs,” he included the peoples who spoke the same language, i.e., Serbs, Bulgarians, Vlachs, Russians, and the northern Slavs who adopted literacy through Great Moravia.

The term “Slavs” refers to those who knew the “letter,” i.e., who read Orthodox books. In the Miroslav Gospel, it states:

“In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God…”

In the Middle Ages, Emperor Dušan’s empire included both Serbs and Bulgarians, who spoke the same language and had rulers who were closely related by family. Later, under the Turks, both peoples remained under one church and spoke the same language until Vuk’s reforms.

Today, one can often hear the term Old Serbian, while Bulgarians say Old Bulgarian. I mention this because knowing Old Slavic makes it easy to read Bulgarian text, which personally helped me read this book and allowed me to go through several hagiographies and the service of Cyril and Methodius.

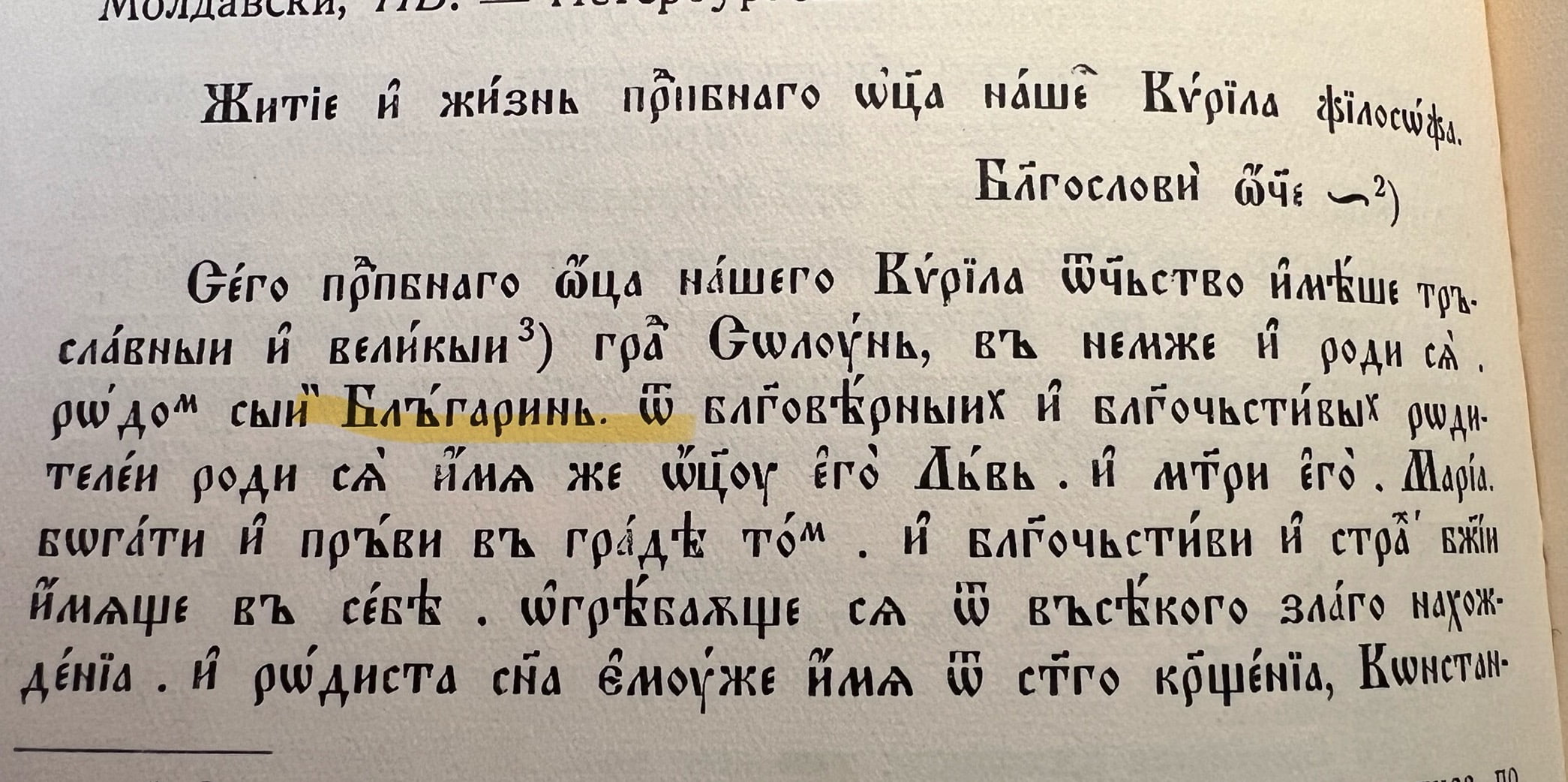

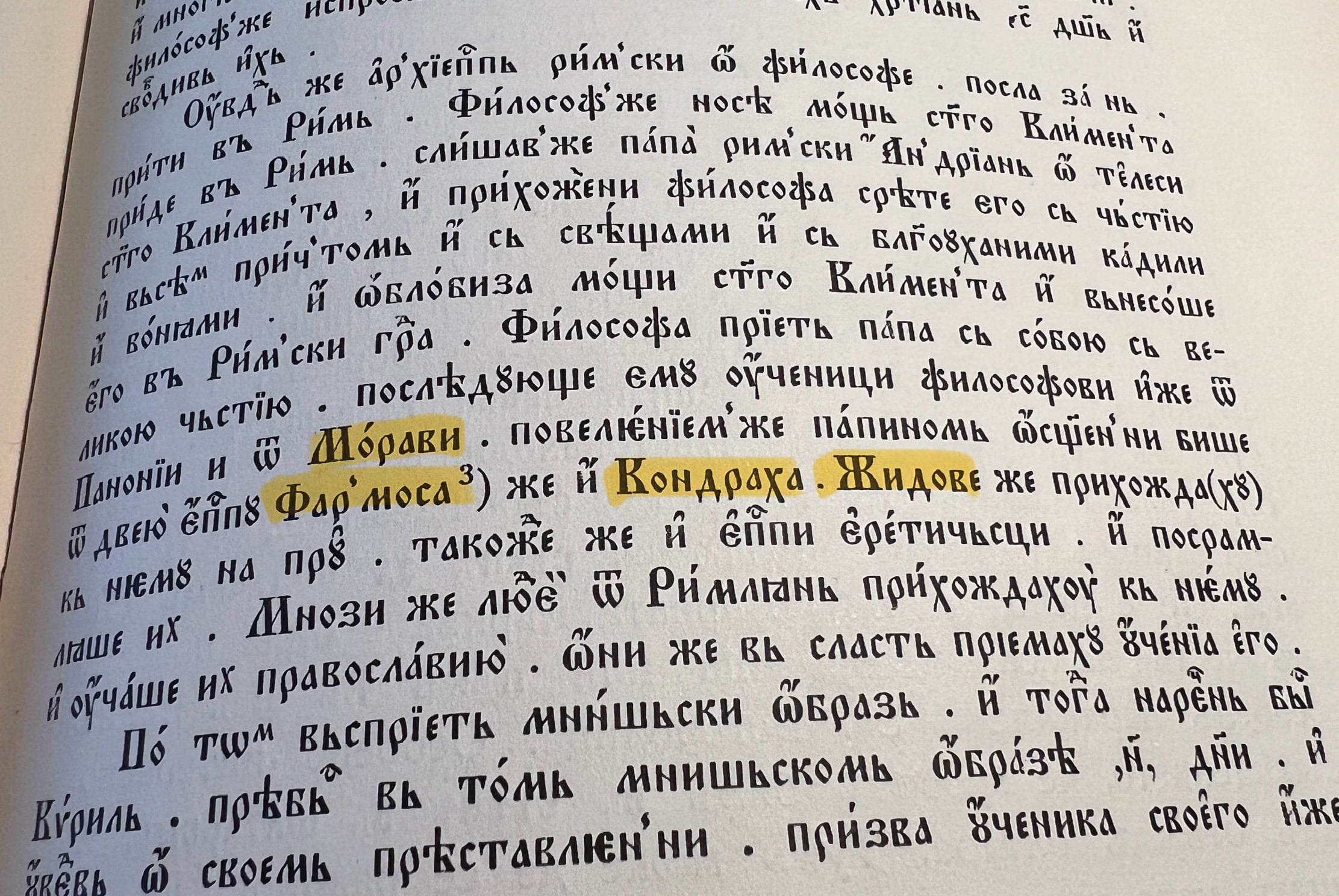

I draw attention to the Hagiography and Life of Our Venerable Father Cyril the Philosopher, a 15th-century Prizren manuscript from the Hilferding collection, published in 1858. When reading this hagiography, one concludes that the official history taught in schools about these two Slavic apostles of enlightenment, Cyril and Methodius, is significantly different.

A Different History of Cyril and Methodius

Cyril’s real name was Constantine, and he was initially a priest, while Methodius was a deacon. They worked on converting the Slavs to Christianity and translating books, i.e., the liturgy and probably the New Testament, into Old Slavic.

Historians are uncertain whether they were of Greek or Slavic origin. However, the hagiography is clear that Cyril was born in Thessaloniki as a Bulgarian, to father Leo and mother Maria. The father was an officer in the Byzantine army, commanding a unit ranging from 400 to 1,000 men.

A lot of nonsense has been written about their hagiographies, and when one scratches the surface, all sorts of things can be found, but rarely the complete truth without interpretations leaning one way or another.

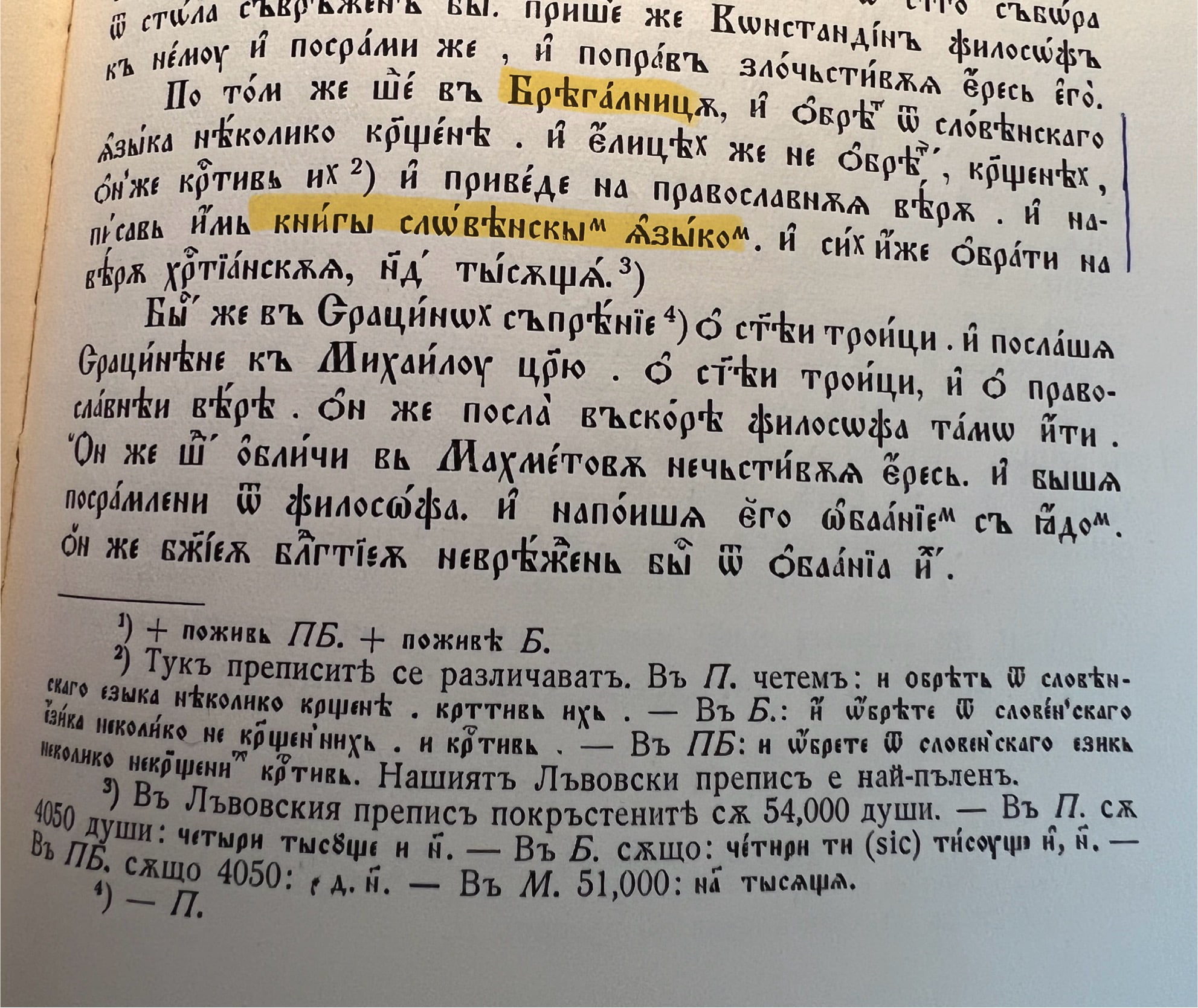

The First Mission on the Bregalnica

An interesting part of the hagiography states that Constantine first went to the Bregalnica in present-day Macedonia, where he converted the Slavs to Orthodoxy and wrote books for them in the Slavic language. The text mentions that he baptized thousands of people, with some other hagiographies citing the 4,050 souls or 54,000 souls (linguists disagree). There is not a word about this in official history. From the writings of Crnorizac the Brave, we know that this happened exactly in the year 855.

Furthermore, from this part of the hagiography, it is clear that he taught them Orthodoxy and discouraged them from Muhammad’s faith. It should be noted that our domestic historians often say that Emperor Dušan was the first to bring Muslims to the Balkans as his alleged allies. Of course, this is not true. Here we have proof that Muslims were present in the Balkans earlier, and there are several other examples and evidence of their presence before Emperor Dušan. Muslims were brought and settled in the Balkans by Emperor Leo IV the Khazar as early as the 8th century.

Furthermore, from this part of the hagiography, it is clear that he taught them Orthodoxy and discouraged them from Muhammad’s faith. It should be noted that our domestic historians often say that Emperor Dušan was the first to bring Muslims to the Balkans as his alleged allies. Of course, this is not true. Here we have proof that Muslims were present in the Balkans earlier, and there are several other examples and evidence of their presence before Emperor Dušan. Muslims were brought and settled in the Balkans by Emperor Leo IV the Khazar as early as the 8th century.

Khazar Crimea and the Jews

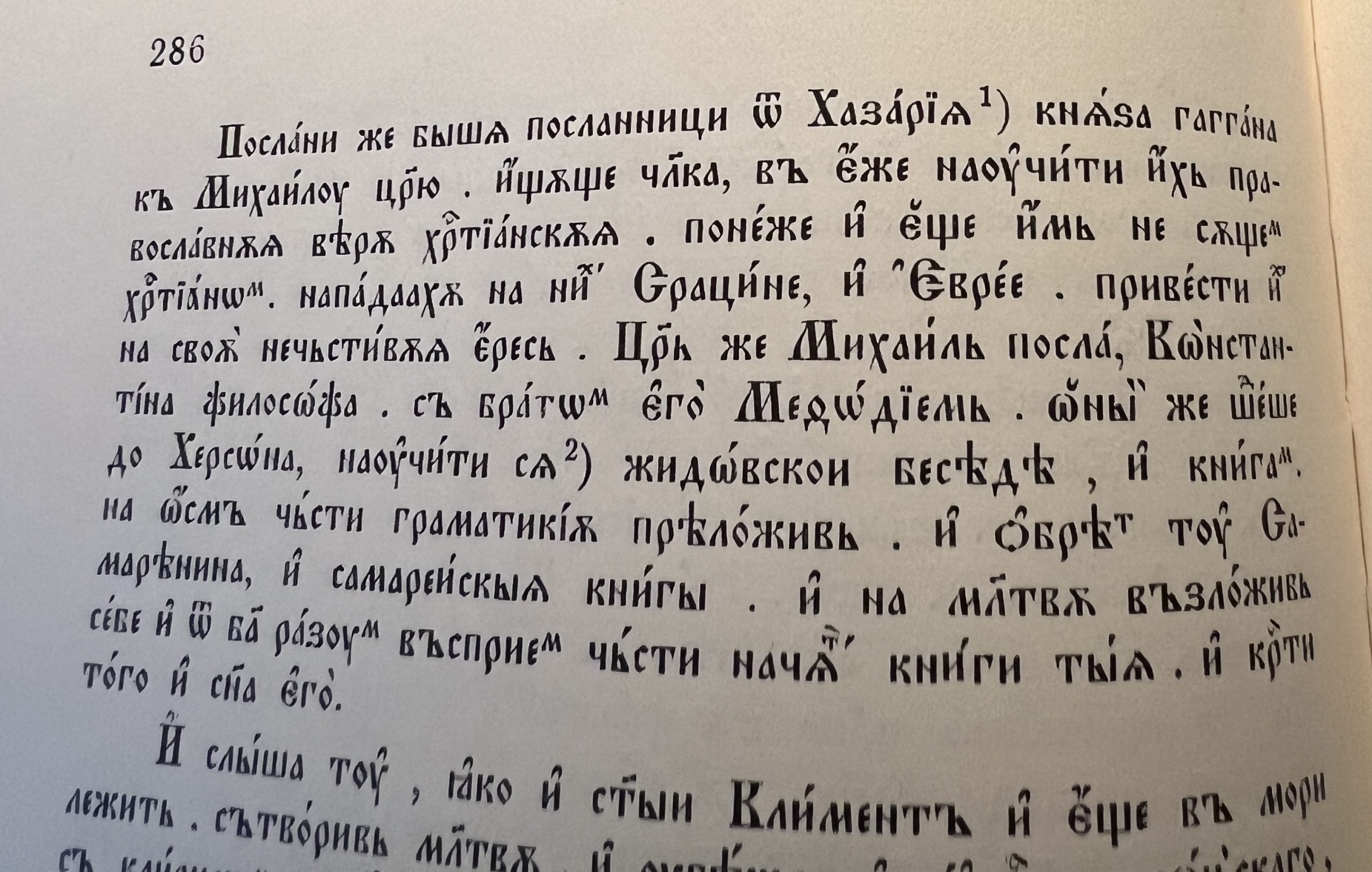

The hagiography states that for their next mission, Cyril and Methodius traveled from Thessaloniki to Chersonesus in Crimea, on the Black Sea. They traveled by ship from Constantinople through the Black Sea to Crimea.

In Cherson, they began teaching the new script, but it is noted that they faced significant issues from the Tatars and from the Jews. It is interesting that no one mentions the Jews on Wikipedia or in historical textbooks.

What is known is that Cherson was the seat of the Khazar Khaganate, which was allied with the Byzantine Empire (Rome). It is also known that a portion of the ruling Khazars practiced the Jewish faith.

There are a few interesting details about the mission in Cherson. It is said that they studied Jewish teachings and books, taught them Samaritan texts, and baptized “him and his son.” Then they heard about the relics of the Christian saint St. Clement, set out to find them, and eventually discovered them. When they found the relics, the Khazar warriors pursued them, but they managed to board a ship.

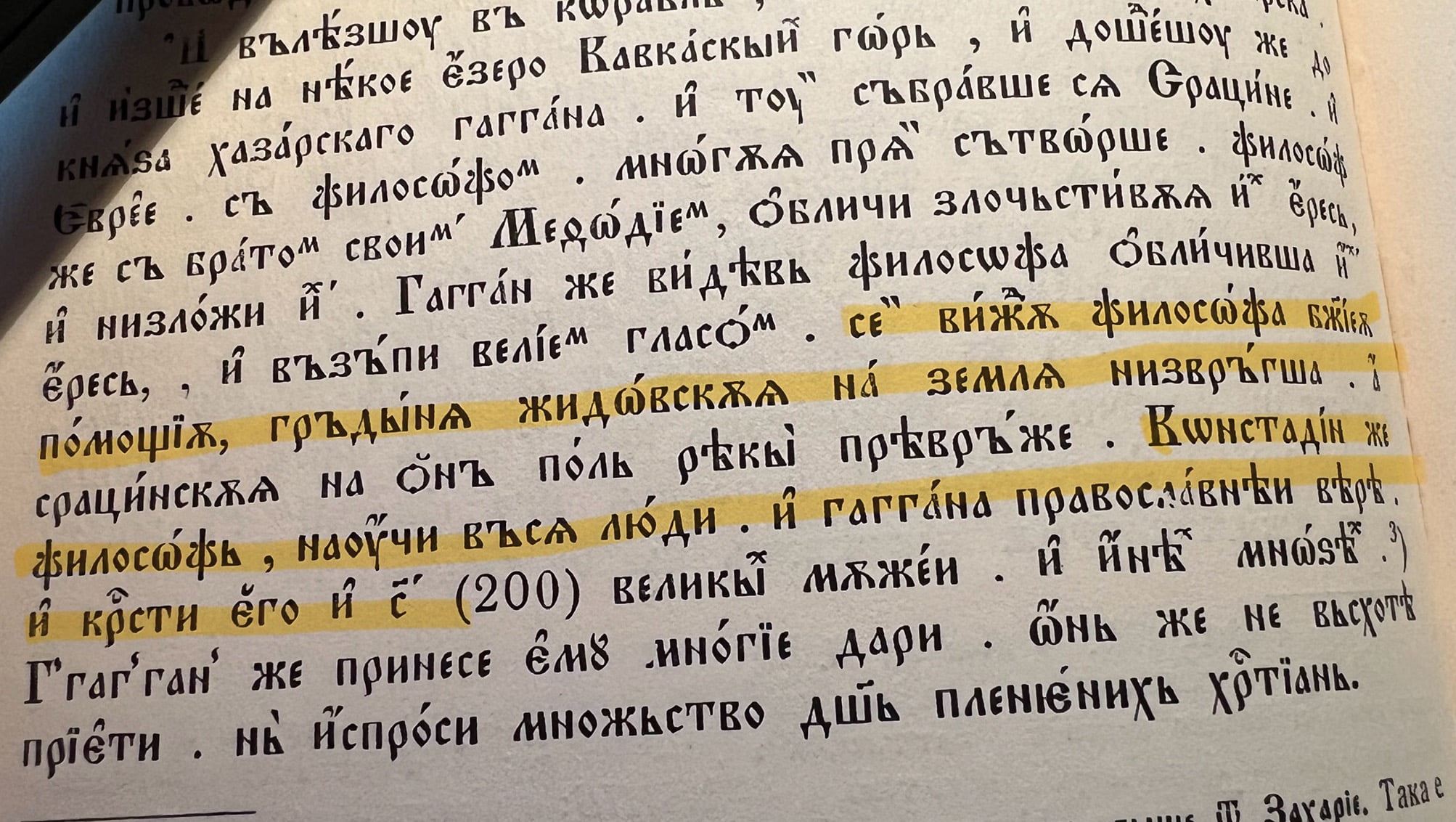

After leaving Cherson, they went “to a lake in the Caucasian mountains” and met with the prince of the khagan, who gathered Saracens and Jews.

The philosopher, along with his brother Methodius, pointed out falsehoods and heresies and explained them. When the khagan saw his explanations, he loudly declared that the philosopher, with God’s help, had exposed the arrogance of the Jews. It further states that Constantine the Philosopher (Cyril) taught all the people and the khagan about the Orthodox faith and baptized him. The khagan showered him with many gifts, and Constantine managed to persuade him to free many Christian slaves.

After this mission, Cyril and Methodius returned to Constantinople (Constantinople). Here, I would like to make an observation. When it mentions “Jews,” it refers to the urban population and traders, as research shows that Jews were primarily among the elite, and there is no evidence that the general population widely adopted that faith. The main sources of income for those Jewish Khazars were taxes collected on the Volga River and at the mouth of the Danube, the slave trade, and minting coins.

Here, I would like to make an observation. When it mentions “Jews,” it refers to the urban population and traders, as research shows that Jews were primarily among the elite, and there is no evidence that the general population widely adopted that faith. The main sources of income for those Jewish Khazars were taxes collected on the Volga River and at the mouth of the Danube, the slave trade, and minting coins.

The rest of the population were Saracens, i.e., Tatars, of Tengrism shamanic beliefs. It is known that the Bulgars and Hungarians who invaded the Balkans and Pannonia were allies of the Khazars. The Russian people, Serbs in the Balkans, and Slavs in Pannonia were subjugated by the Khazars.

The Christianization of the Rus

It seems that this part of the hagiography probably does not refer to the main Khazar khagan but that the “prince of the khagan” was actually some Russian leader who was a vassal of the Khazar Khan from Cherson. Cyril and Methodius converted him and his son to Orthodoxy. This seems logical because, after this, the Rus began their struggle against the Khazars, which Byzantium supported. Russia as a state would form only after Sviatoslav defeated the Khazars.

I would like to point out that this scene from the hagiography is very similar to the later scene in Russian history when, during the time of Vladimir I, a century later, the Rus chose between Islam, Judaism, and Orthodoxy and then chose Orthodoxy.

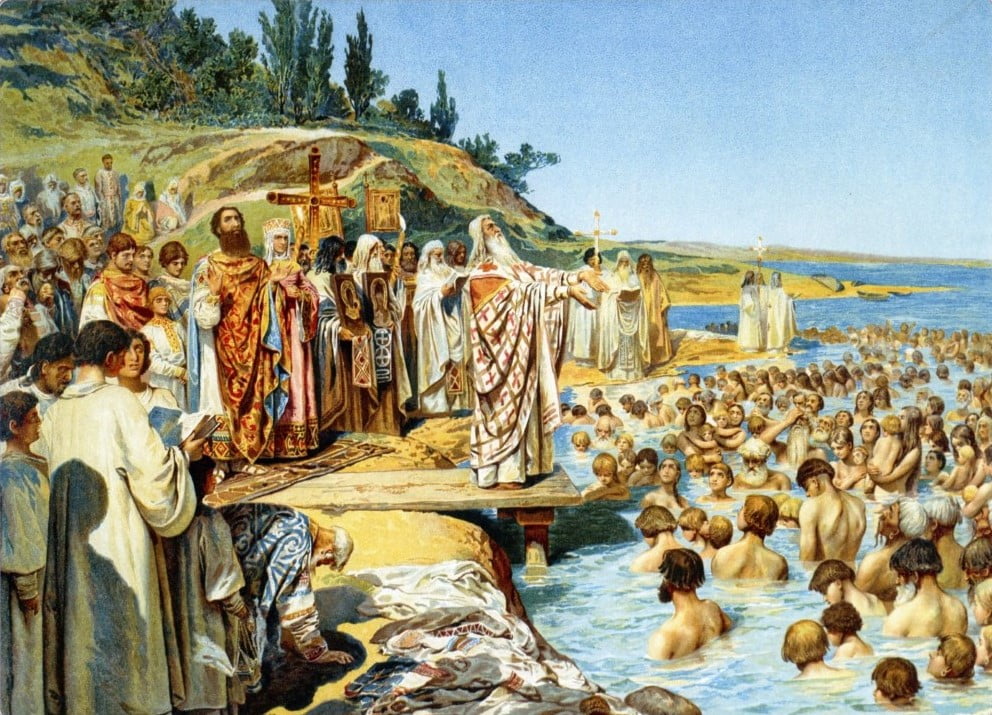

It is certain that the Christianization of the Rus occurred in several phases, beginning with the mission of Cyril and Methodius in 860 and ending in 988 with Prince Vladimir I of Kiev.

Of particular interest to us is Vladimir I’s grandfather – Sviatoslav – as he was the one who defeated the Khazars in Cherson and expelled the Jews. This explains why Crimea is so significant for the Russians today and why there is a war over that territory, with mentions of Khazars and a new Jewish state. Sviatoslav’s victory over the Khazars and their vassals restored control over the Volga River and the taxes collected by the Jews. That the hagiography from Prizren mentions the Jews is no coincidence, as Russian folklore preserves songs about this period and the victory over the “Jewish land” (земля жидовская).

The Khazars and their allies (Bulgars, Hungarians, Pechenegs, Tatars) subjugated the Slavs of the eastern Balkans (today’s Bulgaria), Pannonia (Hungary and Romania), and Russia. In the Balkans, they subjugated the Slavic population and created the First Bulgarian Empire. When discussing the migration of the Slavs to the Balkans, it actually refers to these Bulgars and their auxiliary troops from the Russian-Ukrainian territories. After the mission of Cyril and Methodius, the Slavs of these territories would free themselves from external influences and firmly adhere to Orthodoxy.

After defeating the Khazars, Sviatoslav, in agreement with the Byzantine Emperor, from whom he received 15,000 ounces of gold, launched an attack against the Bulgarians. With 60,000 soldiers and Pecheneg auxiliaries, he attacked Bulgarian Tsar Boris II and defeated him. He captured the Danube Delta, which was the main trade route to Constantinople, and established his main city there. This Russian attack on the Bulgarians, who were Khazar conquerors of the Balkans, led to the weakening of the Bulgarians, which would, a few decades later, result in the fall of the Bulgarian Empire. Then, Byzantine Emperor Basil II defeated Bulgarian Tsar Samuel. This would have a significant impact on Serbian history.

The question arises regarding Khazar Judaism, and it seems it had no connection to the true Jewish tribes but was related to Old Testament teachings and Talmudic doctrine. This religious concept, emphasizing Jewish superiority over Christians and allied with the Vatican and Muslims, bears a striking resemblance to current events in the Middle East.

One might wonder whether Samuel received his name from the Hebrew Shmuel. It is known that Khazar rulers were of the Jewish faith, and the Bulgarians were Khazar allies. Interestingly, Samuel’s brothers were named David, Moses, and Aaron, bearing Old Testament names. So, judge for yourself.

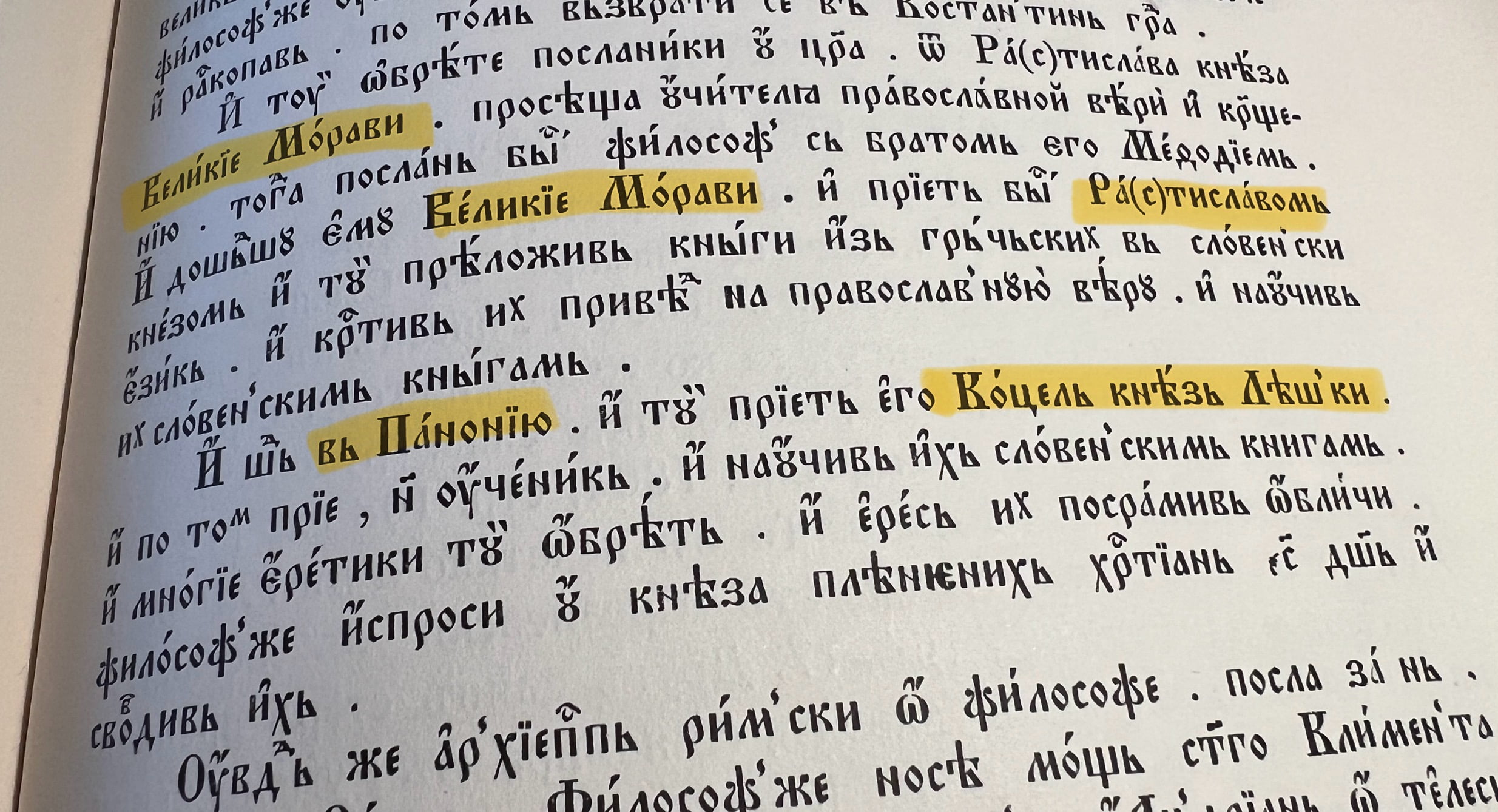

Prince Kocel

The hagiography briefly states that after Crimea, the brothers went to the Pannonian prince Kocel. It describes him as “the prince of Ljessk” (possibly referring to the Lechites – Poles?).

Pannonia is a clear geographical term. It is worth noting that in the Mačva region, there is a village called Koceljevo, known to have been part of the Pannonia province since the 5th century, with its center in Sirmium (Sremska Mitrovica). It is important to remember that Methodius was appointed bishop of Sirmium towards the end of his life and was buried there.

One theory suggests that Koceljevo was named after Prince Kocel. If Cyril and Methodius traveled by ship from Crimea, they could have sailed through the mouth of the Danube, turned into the Sava near Belgrade, and easily reached Koceljevo, which is just a few kilometers from the Sava.

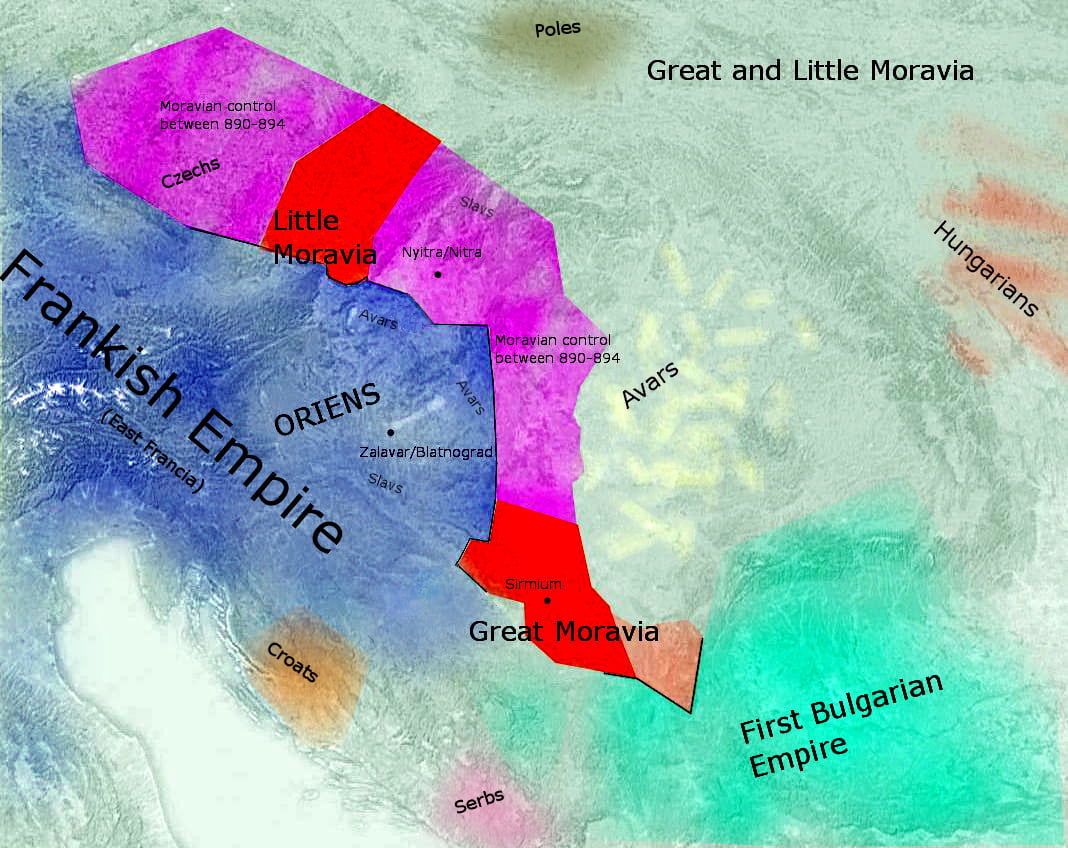

Prince Kocel held part of the territories of Great Moravia, from where literacy spread from the mouth of the Great Morava into the Danube, to the rest of Pannonia.

Kocel’s territories supposedly extended north, but we do not precisely know where the borders were.

The hagiography states that the brothers Cyril and Methodius came to Prince Kocel and “taught them the true faith, turning many heretics to the true faith.” From Prince Kocel, they secured the release of many Christian captives.

Prince Rastislav of Great Moravia

The hagiography further states that when Cyril and Methodius returned to Constantinople, they were met with a letter sent by Prince Ratislav (now often called Rastislav) to Emperor Michael, requesting teachers of the Orthodox faith and baptism for “Great Moravia.” The hagiography continues, stating that Cyril and Methodius brought Rastislav books in Greek and Slavic, baptized him into the Orthodox faith, and taught them using Slavic books.

Now, the question arises: where was Great Moravia? Unfortunately, in our textbooks, it is stated to be somewhere in the Czech Republic and Slovakia, and our scholars tend to accept only Frankish sources in Latin, even though it has been repeatedly shown that these sources are often falsified or fabricated. Sadly, Latin sources are always given more credence, while every comma in our hagiographies is scrutinized under a microscope.

Reading the hagiography leads to the conclusion that Great Moravia was in Pannonia, very likely near the Great Morava River. Fortunately, there are numerous foreign historians who claim that Great Moravia was located in what is now Serbia.

According to the theory of Peter Püspöki Nagy, the central area of Great Moravia was in present-day Serbia, and Great Moravia itself emerged from the union of Slavic tribes — the Bodrići and Slavs settled along the Morava and Timok rivers, who in the 9th century broke away from Bulgaria and came under the protection of the Frankish Empire.

Map of Great Moravia according to Peter Püspöki Nagy’s theory. It begins in Serbia near the Great Morava and expands along the Sava River.

Slovak historian Juraj Sklenár claimed that ancient Moravia was located not only in Moesia (Serbia) but also in Pannonia. He used Constantine Porphyrogenitus as an argument, who stated that Great Moravia was located between Trajan’s Bridge in Sirmium and Belgrade. Sklenár also cited Frankish sources that stated Methodius was appointed bishop of Pannonia.

Slovak historian Juraj Sklenár claimed that ancient Moravia was located not only in Moesia (Serbia) but also in Pannonia. He used Constantine Porphyrogenitus as an argument, who stated that Great Moravia was located between Trajan’s Bridge in Sirmium and Belgrade. Sklenár also cited Frankish sources that stated Methodius was appointed bishop of Pannonia.

He published a book in 1784 in Bratislava titled “Vetustissimus magnae Moraviae situs et primus in eam Hungarorum ingressus et incursus” (Title: The Oldest Location of Great Moravia and the First Invasion and Entry of the Hungarians).

Besides Sklenár, similar theories were proposed by historian Imre Boba, a professor from Washington (USA), who wrote Moravia’s History Reconsidered: A Reinterpretation of Medieval Sources in 1971, Jernej Kopitar, Austrian historian Friedrich Blumberger, Charles Bowles, and Martin Eggers.

Textbooks claim that Great Moravia was based much further north, towards Slovakia and the Czech Republic.

As you can see, some of the greatest historians of the modern era claim what is logical and recorded in the hagiography: that Great Moravia began at the confluence of the Great Morava and the Danube. Yet, this does not prevent our school textbooks and historians from claiming otherwise.

Again, we encounter forgeries and alterations. For instance, our archaeologist Vladislav Popović conducted excavations in Sremska Mitrovica in 1966 and discovered a church that he identified as identical to Methodius’ cathedral. However, he later changed his mind and dated its construction to the 11th century. This puzzling conclusion is pointed out by American historian Imre Boba.

There are also the “Lorch Forgeries,” a collection of papal documents falsified by monks for the Bishop of Passau in 971, which speak of Moravia. In old documents, it states that Moravia was actually in Moesia (present-day Serbia), but a century later, it was moved to Upper Pannonia. This was published by Romanian historian Alexandru Madgearu.

I will not delve further into explaining this issue because I believe it is clear that the contention over Great Moravia has become a political matter. Great Moravia, incidentally, fell due to the invasion of the Hungarians, who were Khazar vassals, further proving how Cyril and Methodius’ mission turned into a religious war where the Slavs fought for freedom from, primarily, the Tatars and Jewish rulers from Crimea, and then for their script and church, which the Vatican and Frankish nobles did not allow.

I created a map of a possible Great Moravia based on older sources, encompassing Moesia with the Great Morava basin and Pannonia, with its center in Sremska Mitrovica.

Great Moravia begins in Serbia in the Great Morava basin, where Kocel was a prince. Old Frankish sources mention Moesia, which is the territory of present-day Serbia.

This relates to the time when Khazar Bulgaria conquered a large part of Serbia. Some people from the Great Morava region moved to what is now Vojvodina and Slavonia, entering into Frankish service. The problem arose when they were forced to adopt the Latin liturgy and script, prompting them to seek help from the Byzantine Emperor, who sent Cyril and Methodius.

Old Frankish sources state that the territory of Great Moravia was in Moesia, i.e., the Great Morava basin and part of Vojvodina with Fruška Gora, extending to the Danube, with its center in Sremska Mitrovica (Sirmium). Fruška Gora is named after the Franks, likely from that period.

The rebellion of Serbs and Slavs against the Khazars from the east and the Franks from the west occurred in compressed Serbia. After the mission of Cyril and Methodius, this cultural rebellion spread through Slavonia and present-day Austria, through the Czech Republic and Slovakia, all the way to the borders of Germany, Poland, and Ukraine.

This rebellion and cultural movement united the proto-Slavs, who had previously been known by various names such as Sorabi, Surbi, Serbs, and Syrbi, with the Czechs, Slovaks, and Lechs (Poles), who all spoke similar languages. For a moment, they all adopted the new name, Slavs. From then on, the old Serbian names gradually faded, and all were collectively called Slavs.

The term “Old Slavic” is not favored by those opposing the unification of the Slavs because the idea of uniting all Slavs is unsettling for the West and the Vatican. Therefore, there is an insistence on a local character, labeling it as “Old Bulgarian” or “Old Serbian.” I believe the term “Old Slavic” is more accurate as it reflects the mission’s goal set by Cyril and Methodius, which was to prevent the conversion of all Slavs.

Old Slavic did not stop at the borders of Great Moravia but spread across all Slavic lands — in territories of present-day Poland, Germany, Russia, Romania, Albania…

The unification of the Slavs around one language in Great Moravia was not well-received by the Vatican and the Franks, nor by the Khazars. The Khazars, with their Turkic-Tatar cavalry, would invade present-day Hungary, while the Vatican would wage bloody conversion wars for centuries to break up the Slavic peoples united around one church and language. The Khazars would be defeated by the Russians, and the Bulgarians converted by the Greeks. The Vatican would convert most of the western Slavic countries — the Czechs, Poles, Slovaks, eastern Germans, Lithuanians, Estonians, and eventually even the Hungarians after the fall of the Khazar stronghold.

The Pope and the Relics of St. Clement

The hagiography states that Cyril received a letter from the Archbishop of Rome, Adrian. Interestingly, it does not call him the pope but the Roman archbishop, as was standard in Orthodox nomenclature at that time. The clear ecclesiastical schism had not yet occurred, though there was already some tension between Rome and the rest of the Orthodox Church.

While in Cherson, Cyril and Methodius discovered the relics of St. Clement I. St. Clement was the fourth Roman bishop, exiled to Crimea by Emperor Trajan as punishment. Clement became influential in Crimea, prompting Trajan to order his death; he was thrown into the sea with an anchor around his neck.

Pope Adrian received these relics as a gift from Constantinople, held a service over the saint, paraded his relics through the city, and eventually placed them in the Church of St. Clement.

The hagiography states that the pope honored Cyril, and many of Cyril’s disciples from Pannonia and “Morava” came to pay their respects. By papal decree, two bishops, Farmos and Kondrach, were condemned. Jews and many heretical bishops came to him, all of whom were shamed. Many residents of Rome came to him and were instructed in Orthodoxy. He then summoned his disciples, Bishops Sava, Angelar, Gorazd, and Naum, to teach them the Orthodox faith, after which he passed away in Rome. He was buried in the Church of St. Clement in Rome.

Exile to Bulgaria

Methodius was summoned to Rome twice to resolve conflicts with the Frankish nobility, first in 873 and then in 878. Frankish sources claim that the pope prohibited the liturgy in the Slavic language. What is certain is that in 878, Methodius was replaced as bishop in Sremska Mitrovica by Bishop Wiching from Swabia, who immediately expelled his disciples. Since then, from the perspective of the Roman Catholic Church, anyone conducting the liturgy in the Slavic language was considered a heretic.

After Methodius’ death, the Norman-Frankish nobility took over the Sirmium episcopate, and then Cyril’s disciples Naum, Gorazd, Sava, and Angelar fled from Pannonia to Bulgaria and established a school near Ohrid to educate future priests. This marked the beginning of the Ohrid Archbishopric.

The Christianization of the Bulgarians occurred in multiple phases. First, Boris I tried to obtain a crown from the pope, leading Byzantium to send a fleet and trigger a crisis that ultimately resulted in Boris being baptized Orthodox. Boris II continued to communicate with the pope, which led to the campaign of the Russian prince Sviatoslav.

Certainly, the greatest Christian influence for the Bulgarians came with the establishment of the Ohrid Archbishopric, as it had the most significant impact on the people.

Where is Methodius’ Grave?

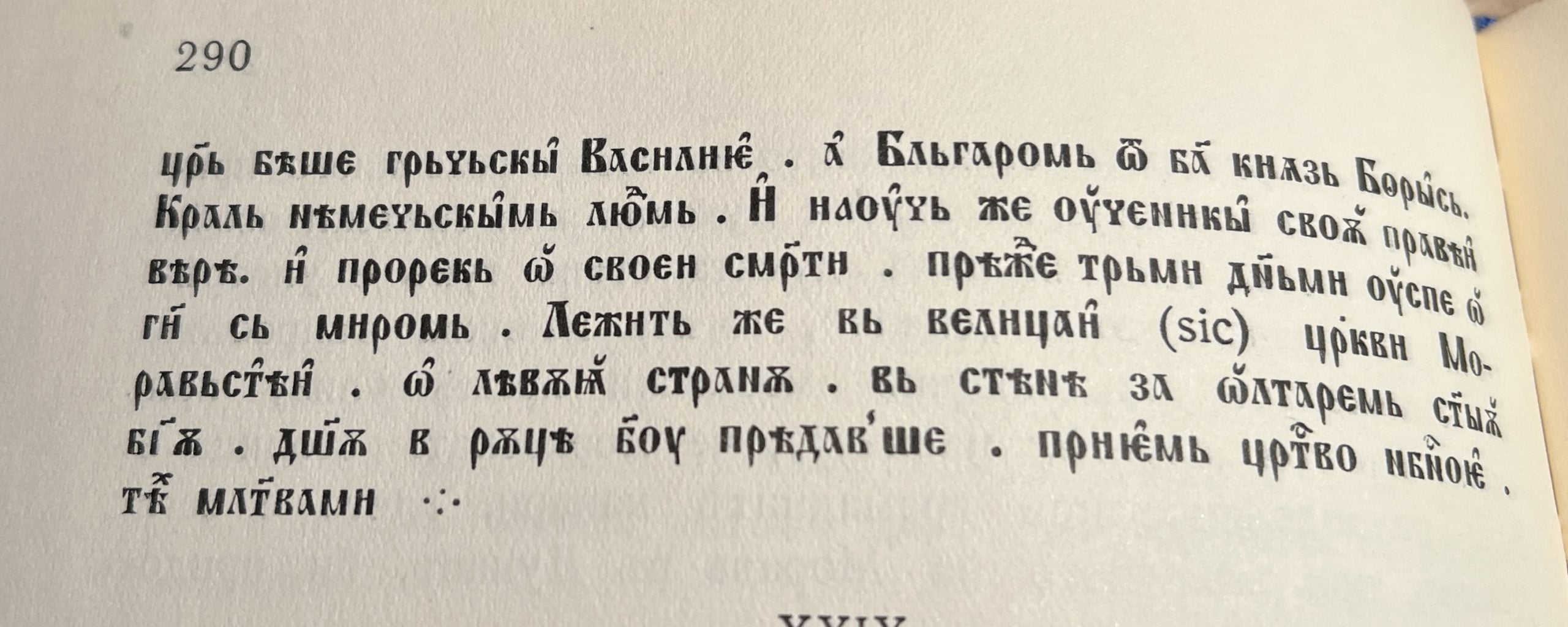

The hagiography states that Methodius was the archbishop of “Upper Moravia.” It is said that (H)Adrian, the Roman pope, appointed Archbishop Methodius to the “throne of the Apostle Andronicus.” The hagiography provides a timeframe, stating that this occurred during the reign of the Greek Emperor Basil and the Bulgarian Prince Boris.

The seat of the Apostle Andronicus was in Sirmium, today’s Sremska Mitrovica. There have already been articles in the media suggesting that St. Methodius’ grave is somewhere in Sremska Mitrovica, but in Jordan Ivanov’s book, I found a detail that analyzes a record in the Prologue Hagiography of St. Methodius from 1330, written in the Lesnovo Monastery. It states that the saint was laid to rest in a large Moravian church and lies in a rock near the altar. Ivanov suggests that this should be somewhere near the confluence of the Morava and Danube Rivers, located near Smederevo and Kostolac.

Given that after Methodius, the Sirmium episcopate was lost to Orthodoxy, as the Roman Catholic Bishop Wiching from Swabia was appointed and expelled all of Methodius’ disciples, it is quite possible that Methodius’ relics were moved from Sirmium to a safer location across the Danube. Therefore, it may be worth searching for the relics in monasteries between Smederevo and Kostolac, as there is a record of Methodius’ disciples crossing the river there.

No Mention of Glagolitic

Although it is said today that Cyril invented the Glagolitic script and his disciples developed Cyrillic, this sounds highly speculative and is not mentioned in the hagiographies. The source for this claim comes from papal and Frankish records.

I would say that the emergence of two scripts, Cyrillic and Glagolitic, on the Balkans indicates a struggle between Rome and Constantinople for influence over the Slavs. This situation would repeat later in the 19th century with Cyrillic and Latin scripts, which disrupted the cultural unity of the Balkan inhabitants.

It is possible that Cyril, who died in Rome and was buried there under the influence of the Vatican, did create Glagolitic, which his disciples spread for a time across the Balkans. I only hope that Cyril was not coerced, kept under house arrest, or slowly poisoned. We may never know, as this is purely my speculation. However, what we do know is that in later centuries, Glagolitic survived exclusively in Croatia within Catholic monasteries. It seems that the strong Nemanjić state rejected Glagolitic and retained the script created by Cyril and Methodius.

There is also a theory that Glagolitic was the script of St. Jerome, but this theory lacks evidence, i.e., any manuscript older than the era of Cyril and Methodius, and none has been found so far.

Conclusion

It is clear that Cyril and Methodius were on a mission to spread Orthodoxy and prevent foreign influences. By translating books into Slavic and allowing the liturgy in the Slavic language, the Byzantine Empire sought to maintain its primacy and prevent the influence of Rome, Jews, and Muslims. The hagiography confirms this.

Many aspects of the Prizren hagiography contradict what is written in textbooks. Cyril and Methodius’ first mission took place in Macedonia; Cyril was of Bulgarian origin, as stated in a Serbian source from the 15th century. They faced issues with Jews both in Crimea and Rome, which is entirely omitted in textbooks. The location of Great Moravia and the territory of Prince Kocel is most likely in present-day Serbia or at least begins there — somewhere between the confluence of the Danube and the Sava and the confluence of the Danube and the Morava. There is also no mention of two scripts; instead, it is clearly stated that they brought Slavic books.

At the beginning, I mentioned that I am a beginner in Old Slavic, and I wonder, if I, as a novice, can read these things that are not mentioned in history, imagine what a serious historian could do if they wanted to or were allowed to. I don’t think it’s due to any particular intelligence on my part, but rather because it’s not popular to think independently and write something that goes against the general narrative in the academic community. This is why we remain in the dark about many things.

Sources:

- Hagiography of Cyril the Philosopher, Hilferding 1858, Serbian manuscript from Prizren, 15th century

- Hagiography of St. Methodius, Stanislav’s Prologue from Lesnovo Monastery, 1330

- Bulgarian Antiquities from Macedonia, Prof. Jordan Ivanov, 1931, Sofia

- Vladislav Popović, *Sirmium – City of Emperors and Martyrs. Collected Works on the Archaeology and History of Sirmium.* Ed. Blago Sirmijuma, vol. 1. Ed. Dušan Poznanović. Sremska Mitrovica: Blago Sirmijuma – Belgrade: Archaeological Institute, 2004.

- Šafařík, Pavel Josef (1863). Sebrané spisy Pavla Jos. Šafaříka, Díl II. Starožitnosti slovanské okresu druhého (in Czech). Prague: Temský.

- Boba, Imre (1971). Moravia’s History Reconsidered: A Reinterpretation of Medieval Sources. Martinus Nijhoff.

Помаже Бог

Где бих могао да нађем да прочитам цело Житије Кирила филозофа, Гилфердинг 1858., српски спис из Призрена XV век. Хвала

Бог нам помогао. Волео бих да помогнем али искрено не знам, то се мора потражити.

Помаже Бог Милоше и Илија. Подстакнут претходним текстом, преузео сам ПДФ верзију књиге ”Бугарске старине из Македоније” и мало је прелистао. Случајно ми је скренуо пажњу коментар 3) на самом дну стране 148 у прегледачу, односно страни 135 у тексту књиге. Чини ми се да је ту дата нека веза између назива Трибал и Србин, али нисам сигуран због непознавања језика. Молим за Ваш превод и коментар.

Унапред хвала!!!

Шаљем један линк, можда не баш директно за ову тему, али сродно. (на руском је, али надам се да неће предствљати неки проблем без превода)

погледајте до краја, интересатно је :

https://www.instagram.com/p/C5yoid6MTRz/