I started with my karate training in traditional shotokan club. Back then, karate was meant for self-defense, wherefore kata was principle method of training. However, several years later, I began to realize that a new, competitive karate, was taking place. Wining medals became the goal and gyako tsuki became main technique, without even thinking of self-defense, while kata practice was considered unnecessary. Soon, karate became empty – to commercial and without essence. By no means, I could not reconcile with the idea that katas are some sort of “mediaeval combat dances” which have no value and therefore I decided to go on with my research by myself.

My research of the ancient Okinawan karate began with thorough reading of Funakoshi’s “Karate do Kyohan” and history of karate. Only then did I realize that I knew nothing at all. I had my hands full of questions and I did not have any answer. What did the ancient Okinawan Tote look like? In what way was it different from today’s karate? To make things worse I had no one to ask that. Still, luckily for me, I found translation of Bubishi. I never imagined that all answers to my questions were written down on Okinawa long ago.

When I first saw the translation of this ancient manuscript, I did not know it would have such influence over my training as well as understanding of the karate art. Here I am about to present a brief analyses, but before I do it, I would like to say that my conclusions are limited by my knowledge, my opinions and my experience. I am practicing Shorin ryu karate and therefore this is view on Bubishi from Shorin ryu perspective. In my research, I have been using English translation by Mr. Patrick McCarthy.

The secret manuscript

The author of Bubishi is unknown as is the date of its making, but with certainty we can say that it existed on Okinawa prior to 1900. It is a sort of compilation of articles on techniques, tactics, vital points, traditional Chinese medicine and ethical code in martial arts. It is unknown whether it is a copy of Chinese book or martial arts school manual. Books like this were quite popular in XIX century China, as today modern self-defense books.

It is certain that many karate masters knew of this book. I will only mention Chojun Miyagi (founder of goju ryu), Gogen Yamaguchi (Japanese goju ryu), Kenwa Mabuni (founder of Shito ryu) and Gichin Funakoshi (“father of modern karate” and founder of Shotokan). There are solid evidence that even great masters Itosu and Higaona possessed Bubishi. However the most plausible source of these writings is probably a Chinese, the master of White Crane[1], Wu Xiangi (1886-1940), better known as Go Kenki. It is a nickname given out of respect meaning “Great respected master”. He lived in Naha and was a close friend and the teacher of Mabuni, Kyoda, Matayoshi, Hanasiro, Kinju Kana and others. Between 1920 and 1930 there was a substantial interest for the origins of the karate art. A group of advanced practitioners gathered around this Go Kenki and studied Chinese system of fighting in order to improve their knowledge. It is possible that Bubishi is a sort of script collected by this group. To support this conclusion I would mention fact that Go Kenki travelled together with Chojun Miyagi several times on Fukien to help him find useful book on self defence and to introduce him to significant masters of Quan fa[2].

The book was kept in utmost secrecy, those who knew of it, copied it by hand. Many illustrations in the book are without description, while the names of the techniques were often written in symbolic poetic language, therefore some parts of it are almost impossible to translate. Even if you spoke Chinese, you wouldn’t understand, because the techniques were not described, but often their symbolic name like “…tiger rushing out from the cage.”

The text is written in Chinese, with very wide usage of old characters that are no longer in use. Back then Chinese was spoken and written only by inhabitants of Chinese colony Kumemura and highly educated people, members of the upper class – pechin[3]. Some of them served as translators in government institutions, for example master Ankoh Itosu was king’s secretary. Why was Bubishi written in Chinese? Perhaps it was a kind of protection from unwelcome curiosity or perhaps out of respect towards Chinese master.

Originally, the chapters in the book are scattered but the book can be divided into four sections: (1) Quan fa origins, history and philosophy; (2) traditional Chinese medicine; (3) vital points and (4) fighting techniques. Id like to say right away that the part in traditional Chinese medicine has no practical use in martial arts today, therefore I want take it into consideration. However, it is obvious that this book had modelled both theory and practice of the ancient Okinawan karate.

The Origins of Karate

Before I begin with analysing the origins of karate art, I would like to point out that in the past, Okinawan karate didn’t look at all as today. Talking from a historical point of view, there are three basic forms of karate:

The first one is today’s sports karate, focused on tournaments. This highly popular and commercial form of practicing developed a few decades ago and has almost no practical value in self-defence. Then, if we move further into the past, well come across traditional karate (karatedo) with its principal aim – recreation, pre-military preparation in Japan before WWII. For the development of karatedo, masters Ankoh Itosu and Gichin Funakoshi are the most deserving ones. It appeared around 1900 and presents a very efficient system of self defence focused on its applying in practice. Bubishi therefore talks about Tote jutsu, i.e. karate before it became karatedo and before it become sport. Tote jutsu is Okinawan method of self defence, kept in secrecy being taught only to individuals strictly within the pechin class, which relied equally on punches, joint locks, throwing techniques and usage of weapons. This method was modelled by generations of man who practiced it – warriors, by combining traditional Okinawan method of fighting (te) and different Chinese styles or fighting from neighbouring Fukien province. And out of which style was karate formed?

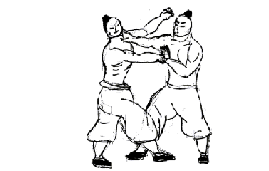

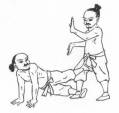

By studying Bubishi we can easily draw a conclusion that the basis of karate is the White Crane style. The creation of this style as a combination of the techniques of the Crane and Tiger styles was described at the very beginning of the book. This was even illustrated in the article #28, where a woman was presented while performing Hakutsuru no kamae[4] while a man was presented in position characteristic for Tiger[5] style. This symbolic uniting of female (soft, ju, jin) and masculine (firm, go, jang) style resulted in creation of a perfect method of fighting, according to manuscript. Bubishi however isn’t only about White Crane style, but also mentions such styles as: Monks Fist, White Monkey, Tiger and Drunken Man. This as a definite proofs that karate is an eclectical system, i.e. a combination of most efficient techniques and principles of several quan fa styles. This hypothesis is confirmed by many prominent masters in their writings (Ankoh Itosu, Chojun Miyagi, Gichin Funakoshi, Kenwa Mabuni).

Illustration of the article #28, a woman is presented in the position of the crane, whereas man is in the position of a tiger. The picture symbolizes the metaphysical unity of these two principles of fighting.

It may be concluded that karate was formed by combining five most famous quan fa styles of that time Crane, Tiger, Monk Fist, Monkey and Drunk man style). This also corresponds to esoteric principle of Chinese numerology (five elements or style of five ancestors).

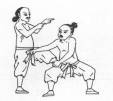

I would like to comment on the basic idea of karate, i.e. the uniting of the Crane and the Tiger. This is described at the very beginning of Bubishi, namely in the duel between Fang Jinyang (a women who was a master of the Crane) and Zheng Chisu (the famous master of the Tiger), nobody won Fang used evading, deception and precise blows into vital points, but didn’t have enough strength to beat Zheng, who was stronger. On the other hand, Zheng used direct punches, powerful techniques, but couldn’t give any efficient blow. Eventually, love was aroused between them and they created the invincible style White Crane, which benefited from the good principles of both styles. This story shows that a style based on one sort of techniques exclusively cannot be perfect.

Fang Jiniang attacks the crane with a pole and by observing his reactions she adopts the principles of style White Crane.

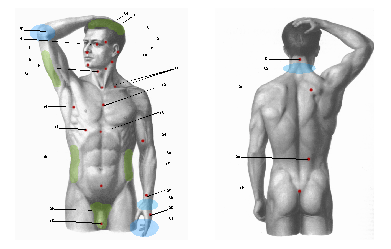

36 vital points

There are several articles in Bubishi, which are referring to punching painful points of human body – kyusho. The text mentions Bronze man[6] statue, so we can conclude that this sphere of fighting was regarded with great seriousness that is a scientific method of that time was applied by relying on traditional Chinese medicine. The positions of the vital points ware described by using a specific acupuncture point on the statue.

The whole chapter is full of legends of circulation of life energy (ki), of punches with delayed reactions (shichen) or “touch of death” (dim mak). Its very difficult to say whether it is a sort of encrypted text impossible to translate today, or the written material is full of myths, owing to limited knowledge of physiology of human body at that time. The chapter is not homogenous, for example, one article is about classification of vital pints according to acupunctural points, another is about points based on experience and observation, while third article names the points that can be activated only by means of weapons[7].

There are several versions of Bubishi manuscript and all of them differ among themselves more or less[8]. It is most visible in the chapter on vital points. Some versions have certain articles excluded whereas in some only the points mentioned are different. Number “36” is very important in Chinese numerology, but in reality it is not final number of vital points. The interesting thing is that the text itself doesn’t describe precisely how to punch a vital point, which leads me to conclusion that the author was already familiar with the information, that is, the article served as a kind of script or reminder. The differences between some of the versions occurred probably because of difference in understanding and applying of knowledge in reality. In this article, also, I’ve give a list of vital points limited by my understanding, opinions and experience.

There is almost no applying of knowledge if vital points for majority of today karate clubs. Instructors basic concern is “…how to win a match?” and therefore “almighty” seiken surface is primal weapon with only a few of simple techniques practiced. To make things worse, fist punch to chin is often thought as basic technique, which is very dangerous in reality because one may easily break the bones of the hand.

To understand this section of karate correctly, it is necessary to observe things from the perspective of practical self-defence. In the street, as a rule, the attacker is stronger than you are, so you must make your punch worth twice as strong. You will achieve this if you cunningly hit the opponent in the most painful points. Therefore the knowledge of basic anatomy and physiology of human body is essential.

Apart from knowing the spot where to hit, one should know how and with what to do so. Random punching with fist won’t do any good. The greatest efficiency is achieved when the striking surface and technique are adjusted to the vital point. Besides the fist, it includes the use of palm, ridge hand, finger pokes, tearing, pinching, and pressing… This is described particularly in the article #20, “Six hands of Shaolin“. There are suppositions that the article had inspired master Chojun Miyagi when he formed Tensho kata out of some longer Chinese kata.

| Vital point | Application | Sources |

| 1. Top of head | Hammer fist strike (tetsui) | Karate do Kyohan – tento Bubishi, article #24 “Bronze Man Statue”, GV22 |

| 2. Back head and ears | Open hand slap (teisho) | Bubishi, article #24 “Bronze Man Statue” |

| 3. Temples | Ridge hand (shuto) strike and one knuckle fist (shoken) | Karate do Kyohan – kasumi Bubishi, “36 Vital Points”, GB3 |

| 4. Eyes | Finger poke | Karate do Kyohan – gansei Bubishi, article #17, “Seven Restricted Locations” |

| 5. Nose (philtrum) | Hammer fist strike (tetsui) | Karate do Kyohan – uto Bubishi, “36 Vital Points”, GV26 |

| 6. Chin | Forceful open hand thrust can dislock jaw or injure neck (teisho) | Karate do Kyohan – gekon Bubishi, “36 Vital Points”, CV24 |

| 7. Mastoid process | Hammer fist (tetsui) strike or ridge hand (shuto) strike | Karate do Kyohan – dokko Bubishi, “36 Vital Points”, TH17 |

| 8. Posterior midline | Head manipulation or neck breaking techniques (1-2 vertebrae) | Karate do Kyohan – keichu Bubishi, “36 Vital Points” & article #17, “Seven Restricted Locations” |

| 9. Throat | Choking technique (shime) or forceful grab can seriously hurt person (nukite) | Bubishi, article #17, “Seven Restricted Locations” |

| 10. Neck (carotid sinus) | Ridge hand (shuto) strike and finger stab (nukite). | Karate do Kyohan – matsukaze Bubishi, “36 Vital Points”, ST9 |

| Vital point | Application | Sources |

| 1. Jugular and sternal notch | Finger jab “Cranes beak” (kakushiken) | Karate do Kyohan – murasame & hichu Bubishi, “36 Vital Points”, CV22 & ST12 |

| 2. Breast bone (anglus sterni) | One knuckle fist (shoken) or elbow smash | Karate do Kyohan – tanchu Bubishi, “36 Vital Points”, CV18 |

| 3. Xiphoid process | One or two knuckle fist (shoken or hiraken) | Karate do Kyohan – yosen Bubishi, “36 Vital Points”, CV15 |

| 4. Armpit | One knuckle fist (shoken) | Karate do Kyohan – kyoei Bubishi, “36 Vital Points”, HT1 |

| 5. Ribs | One knuckle fist (shoken) | Karate do Kyohan – genka & denko, Bubishi, “36 Vital Points”, GB24 |

| 6. Floating ribs | Open hand thrust (teisho) or hammer fist strike | Karate do Kyohan – inazuma Bubishi, “36 Vital Points”, LIV13 |

| 7. Abdomen | Thrusting kick (sokumen or teisho) | Karate do Kyohan – matsukaze Bubishi, “36 Vital Points”, ST9 |

| 8. Groin | Upward kick (kinteki geri) or palm smash (teisho) | Karate do Kyohan – kinteki Bubishi, “36 Vital Points”, LIV11 |

| 9. Tip of the Coccyx | Knee kick (hiza geri) | Karate do Kyohan – bitei Bubishi, “36 Vital Points”, GV1 |

| 10. Lumbar area | Knuckle fist (hiraken) or knee (hiza geri) | Karate do Kyohan – ushiro denko Bubishi, “36 Vital Points”, BL51 |

| 11. Above shoulder blade | Ridge hand (shuto), hammer fist (tetsui) | Karate do Kyohan – hayauchi Bubishi, “36 Vital Points”, BL43 |

| Vital point | Application | Sources |

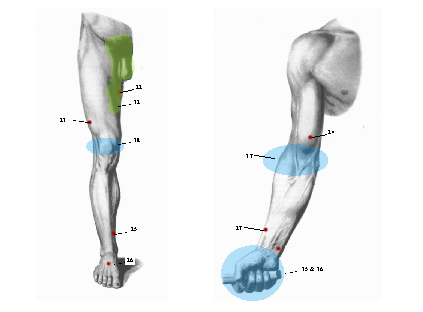

| 1. Thigh (inside) | Thrusting kick (sokumen) | Karate do Kyohan – yako |

| 2. Thigh (peronal nerve) | Snapping kick (sokumen geri) or knee kick (hiza geri) | Karate do Kyohan – fukuto; Bubishi, “36 Vital Points”, GB31 |

| 3. Biceps | Ridge hand (shuto) strike | Karate do Kyohan – wanjun; Bubishi, “36 Vital Points”, LU3 |

| 4. Shins | Snapping kick (nami gaeshi) | Karate do Kyohan – kokotsu, |

| 5. Foot | Stomping kick (fumikomi) | Karate do Kyohan – soin; Bubishi, “36 Vital Points”, LIV13 |

| 6. Forearm | Ridge hand (shuto) | Karate do Kyohan – sotoshakutaku; Bubishi, “36 Vital Points”, LI10 |

| 7. Back of the hand | Knuckle fist (hiraken) | Karate do Kyohan – shuko; Bubishi, “36 Vital Points”, TH2 & LI4 |

| Vital point | Application | Sources |

| 1. Testicals | Tuite technique, grab testicles, twist and pull. | Bubishi, article #17, “Seven Restricted Locations” |

| 2. Abdomen side | Tuite technique, tearing of abdomen (“love handles”) skin. | Bubishi, article #17, “Seven Restricted Locations” |

| 3. Triceps | Tuite technique, tearing of triceps skin. | |

| 4. Inner thigh | Tuite technique, tearing of inner thigh skin. | |

| 5. Neck | Control (shime), various choking and holding techniques. | Bubishi, article #17, “Seven Restricted Locations” |

| 6. Hair | Easy way to control your opponent is to grab his hair. | |

| 7. Fingers | Finger locks (kansetsu) | |

| 8. Wrist | Wrist locks (kansetsu) | |

| 9. Elbow | Elbow locks (kansetsu) | |

| 10. Knee | Knee locks (sokuto geri) |

48 fighting techniques

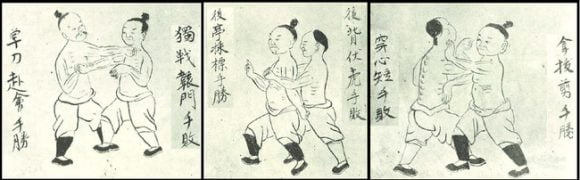

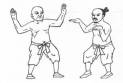

According to the opinions of many experts, the article “48 techniques” is one of the most important ones in the whole Bubishi. However, the understanding of this text is not easy at all. Firstly, the sketches of the techniques are sometimes obvious, but sometimes it is almost impossible to understand what they are about. In few places the techniques appear repeated. I believe this is a mistake done while copying the book, because the logical conclusion is that the author wouldn’t repeat the same techniques. Their names are symbolic and have no connection with modern karate terminology.

The illustrations of 48 techniques are very inspirative and without any doubt everyone devoted to karate will benefit from studying this article. This chapter could be named “Bunkai catalogue” because the article presents the techniques, ideas and principles of fighting found in all Okinawan katas.

Last 9 illustrations, in my opinion, are different from others. They don’t show actual combat applications, but describe basic principles. So, illustrations 40-48 are “ABC of fighting”: vital points (kyusho), body change (tenshin), distance (maai), formlessness, focus (kime), simplicity, control, decisiveness (zanshin) and feints.

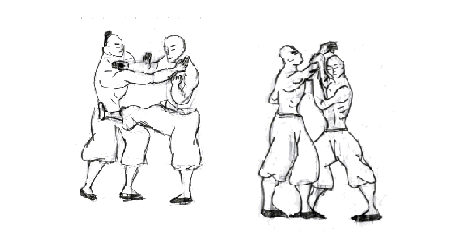

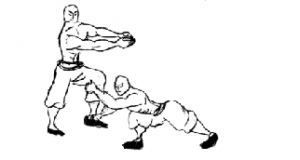

Illustration #1 (“48 techniques”, #26), the point is to let opponent to pass and then taking him down. Illustration #2 (“48 techniques”, #14), arm bar.

What did the ancient karate look like?

By careful examination of Bubishi, we are able to reconstruct the ancient Okinawan karate – tote jutsu. The most useful information are in the section dealing with vital points, then in the article on 48 techniques, as well as in article #16, “Grappling and Escapes”[9]. I took liberty to illustrate a few techniques, which are in Shorin katas with applying of principles from Bubishi. Therefore what useful information can we draw from this article, in order to apply them in our training?

In ancient Okinawan karate, hand techniques are apparently the most important. To support this ill mention an old name for karate – tote, (“Chinese hand”). When executing hand techniques, almost all surfaces are used: (1) fingers (four fingers – nukite; one finger – ipon nukite; “cranes beak” – kakushiken), (2) palm (teisho), (3) ridge of hand (shuto), (4) fist (knuckle fist – hiraken; one knuckle fist – shoken; hammer fist – tetsui), (5) elbow – empi, as well as grabbing techniques (torite) by testicles, throat, hair, triceps or thigh.

It is interesting that the use of fingers and palm surpasses the use of the fist. The predominant use of the fist today is probably a result of the changes made by master Itosu, when karate was included into the educational program on Okinawa. Namely, the palm and the fingers are very efficient, but the use of the fist decreased the possibility of injury of younger trainees. Special attention is given to practicing of techniques with open palm in the article #20, “Six hands of Shaolin”.

Rokkusho, that is “6 palms of Shaolin” presents: (1) ridge hand (shuto), (2) palm (teisho), (3) fingers (nukite), (4) “grabbing hand”, (5) “Cranes beak” (kakushite) and (6) one finger poking technique (ipon nukite).

Picture 1., The technique is used to demonstrate the defense against the most usual type of attack, when the attacker reaches his arm in order to hit, seize or push. Arms are raised in a defensive position and moving away from the direction of attack is performed, then comes grabbing and a hit with ridge hand (shuto) into the neck (carotid sinus). In my opinion, this technique is presented in Bubishi, “48 techniques”, #6 and is drawn from kata Kushanku.

Picture 2., “Phoenix spreads his wings” (“48 techniques”, #32), a very interesting technique, showing the use of the fingers in a fight parrying of opponents punch/grab and then trust with fingers into the eyes. In my opinion, this technique is found in many katas. Here presented sequence is drawn from kata Patsai (Kyan no Patsai).

Picture 3., the use of ridge hand (shuto uchi) and the base of palm (teisho tsuki) are widespread in tote jutsu and shown in Bubishi (#19, #31, #35).

Picture 4., The smash or tearing of the testicles are amongst the most efficient techniques of Okinawan karate. Here are shown two different techniques. In firs one, grabbing is done from the outside while holding the opponents arm, which prevents the attack by other arm. In the second, picture a sudden attack shown in the kata Kushanku (ura kamae). This technique is shown in Bubishi (#36).

Picture 5. Okinawan karate makes use of the elbow in several different variants. Almost all katas contain elbow strikes and proof for this can be found in Bubishi (technique #39). Here is presented sequence from kata Kushanku. Firstly, one parries the opponent attack with an arm or knee, and then he grabs opponents back of the head and smashes his face with elbow.

It is interesting to see that leg techniques were not considered very efficient. Support for this statement lies in fact that the attacker always loses when he tries to kick the opponent (illustrations #5, #13, #21 and #16). I think that kicks were thought of as supplemental, being done to ease the performance of the arms. Still, it could be concluded that knee (hiza geri) and front kick (mae geri) as well as different ways to put opponent out of balance (#3, #9, #20 and #31) were used. What can be observed with certainty is the absence of attractive kick such as mawashi, yoko and ushiro geri, so widespread presented in karate today.

Picture 6. Regardless of being shown explicitly in the article on “48 techniques” kicks are also mentioned in the article #16 “Grappling and Escapes” (#15, #17, #18 and #23), so it could be concluded that different variants of mae geri and hiza geri were two most important leg techniques. Beside this tote makes use of stomping kicks.

It is important to perceive that in tote jutsu there is a wide applying of techniques that are absent from karate sport today: joint locks, throws, chokes, grappling, ground fighting… Actually, the whole article on 48 techniques is some kind of recommended frame or concept of ancient fighting art, that is techniques, as well as situations and fighting principles, are shown.

Regardless of the style, tradition or kata you are practicing, you can look in for bunkai (practical application of kata movements) in the article on 48 techniques or the article #16, “Grappling and Escapes”. I think this is very important, because now we can positively see that joint locking, throwing and grappling are essential part of karate.

When talking of joint locking techniques there are: lock on the wrist (#2), lock on the elbow with pressure, over the shoulder or by twisting the arm (#8, #14, #28, #31 and #39) and lock on the knee (#18). A great number of techniques making use of specific vital points to cause pain to the opponent by pressing or tearing are being used (tuite[10]). Firstly, there is eye gouging (#19, #32 and #35), tearing of the larynx (#13 and #15), grabbing of testicles (#36, #33, #27 and #15). Also there are less dangerous, but equally painful actions: pinching by the skin on the triceps (#14), skin tearing on side of abdomen (#30), ribs below the nipples (#40), skin tearing of inner thigh (#12) and hair pulling (#4 and #33). There is substantial number of throwing usually done by taking opponents leg when he tries to kick (#5, #21 and #22) or by simple catching of the opponent’s leg when it is possible (#12). Also, a few classic throws are demonstrated (sukui nage #11, osoto gari #17 and ashi barai #31), also sacrifice throw (tomoe nage #24) and entangling of the legs while laying on the ground – “scissors throw” (kani basami, #3 and #9). I would especially mention the technique of head manipulation, which can be used to knock the opponent down; but if done forcefully becomes a lethal technique – breaking of the neck (#4).

Picture 7. This is my personal interpretation of the illustration #2 (“White monkey stealing fruit – Black tiger rushing from the cage”). I think that the correct explanation of this technique is similar to the situation shown in the opening movement of the kata Patsai and that is escaping technique when opponent is holding your arm.

Picture 9. Head manipulation technique (“48 techniques”, #4) is an efficient way to bring your opponent down. This movement can be found at the beginning of kata Patsai.

Picture 10. One of basic throws in karate. The popular name is osoto gari, also Funakoshi uses Okinawan name byobudaoshi (Karate do Kyohan) and there are several different variants of this technique. Bubishi, “48 techniques”, #17, also can be observed in kata Kushanku, Naihanchi and Wanshu.

Picture 11. The throw that I prefer to call sukui nage is variation of throw presented in Bubishi (#11 or #22). It can be done by grabbing opponent’s testicals, also. Similar throw is in kata Wanshu (Empi), (kosa dachi – gedan tsuki, and then gedan barai).

Picture 12. The throw by grabbing the opponent’s leg. It is in kata Kushanku and is shown in Bubishi (#18). When the opponent hits the ground, you should hold his leg in your hands and stomp on his groin.

Picture 13. When the opponent attacks from behind, firstly you should attempt to grab his genitals (“48 techniques”, #27) and then step behind him and throw him down (“On grappling and escaping”).

Picture 14. This is my interpretation of technique from kata Unshu (Unsu), therefore I call it unshu geri. It is presented in “48 techniques” in two variants; the first one is shown here (#3) and the other one is when attacker comes from behind (#9). Firstly, a shock kick into the groin is used and then there is entangling technique to bring opponent down.

Picture 15. This is demonstration of throwing when the opponent’s leg is captured during the kick. This is actually the applying of the simple gedan barai and can be found in kata Patsai. In Bubishi, there is an illustration #21 (or #22).

Picture 16. This technique is variant of previous one (gedan barai – kata Patsai), but executed from inside. Leg is usually followed by a punch with an arm, it is important to grab both the leg and the arm, so that you can safely throw your opponent.

At the vary beginning the Okinawan peoples were using a term “tote jutsu” for karate. Translated it meant “the method of the Chinese Hand”, which is common name for Chinese quan fa.

Bubishi confirm the theory that karate is civilian fighting art, i.e. karate as a method was not meant to be used in the battlefield, because that would make training methodology completely different from as it is today. It was not supposed to serve to the Okinawans to defend against a samurai armed with katana, because it is equally pointless as training of bare hand defense against the attack of fully equipped US marine. The goal of karate training is to teach how to defend yourself against the most usual types of attack.

Most often, the attacker is someone familiar to us, most probably a friend, an acquaintance or a member of a family. Therefore, the attacker is someone not professionally trained for fighting (like a member of the army, riot police or samurais). The most common type of attack a couple hundred years ago on Okinawa is the same as the common attack today. So, karate as self-defense system can be used today as it was on Okinawa several centuries ago. Article “48 techniques” represents these acts of habitual physical violence: punching (#12, #31, #30, #34, #36), pushing (#14, #40), seizing and punching (#13), hand attack combination (#12), kicking (#5, #21, #22), kick and hand attack (#26), as well as escaping techniques when opponent tries: bear hug (#1, #4), arm holding (#2), leg catching (#10), hair pulling (#15), headlock (#33), bear hug from behind (#27), seizing lapels (#38). All instructors should consider these situations when teaching basic kumite.

The conclusion is that karate, as we know it today is different from the original style before 1900. The examples and proofs for this are in Bubishi. Since the history of this martial art is incomplete owing to oral transmission of knowledge and secrets, the value of this document is immeasurable. We can say that the essence of the ancient karate is forever preserved in Bubishi. This unsystematic collection of different articles from history, vital points, traditional medicine and practical applications is best reference for studying the history of karate. Just as we can look kin the cooking pot and see all the ingredients we can treat Bubishi as a kind of receipt, rough sketch or script and say that rightfully deserves name – The Bible of Karate.

Feng Huo Yuan, guardian of Fujian, third son of an powerful Chinese god of war, disciple of combative disciplines. Representing virtue, propriety and perseverance.

Footnotes:

- White Crane is Quan Fa style, which made greatest influence on development of Okinawan karate.

- Quan Fa is general term for various kung fu styles and traditions. Wu shu is term used to name modern styles developed after Chinese communist revolution.

- Historian Patrick McCarthy has proved that stereotypical conception that “subjest peasants” had developed karate is unlikely. It had been done by members of Pechin class (noblemen, kings guard, village militia, prosecutors…).

- Hakutsuru no kamae, the position of White Crane can be found in many katas of Shorin ryu as in other Okinawan styles.

- This position is typical for kata Useishi (the modern name is Gojushiho), whose name when translated means “54 footsteps of the Black Tiger”. This is actually opening movement of this kata.

- Chinese emperor Ren Zong, ordered court chief physician in 1026 to make two precise models of man, on which, acupuncture points and meridians could be precisely presented. In that way was created a standard for the whole Chinese empire, which is still in medicine use today.

- Fernando P. Camara, Analysis of the Okinawan Bubishi (October. 1997.)

- According to the analyses of Joe Swift and Victor Smith

- According to Patrick McCarthy this text as a whole is in Funakoshi’s, “Karate Do Kyohan”, namely at the end of the chapter “Maxims for the trainee”, there is a part in old Chinese, Tsutomu Ohshima said that he was unable to translate. That whole text in Chinese was actually taken from Bubishi (article #16).

- Tuite is a term used by many martial arts enthusiasts for very painful hand techniques of finger poking, pressing, tearing, pinching and grabbing.

Bibliography

- Bubishi – The Bible of Karate, Patrick McCarthy, Tuttle 1997.

- The 48 Figures of the Okinawan Bubishi by Fernando P. Camara (lecture)

- Bubishi by Joe Swifth (article)

- Bubishi by Victor Smith (article)

- Bubishi by Ernest J. Estrada (article)

- Karate-do Kyohan by Gichin Funakoshi

- The Essence of Okinawan Karatedo – Shoshin Nagamine

- Fukien Shaolin White Crane Kung Fu – article by Paul de Tourreil

- Targets by Joseph R. Svinth

- Bunkaijutsu – article by Patrick McCarthy

- Technique – Chojun Miyagi (essay)

- Crime and Violence by Joseph R. Svinth

Trackbacks for this post